Cardiac Arrest Overview

Cardiac Arrest Overview

The algorithm for adults in cardiac arrest goes over the evaluation and treatment of patients with no detectable pulse who are not resuscitated using basic life support (BLS) treatments.

The most important aspect of the algorithm is high-quality CPR with minimal interruptions.

There are two pathways for responders to follow:

- Cardiac arrest with shockable rhythms (VF and pVT)

- Cardiac arrest with nonshockable rhythms (asystole and PEA)

Related Video: One Quick Question: What to Expect During Your First Code?

ACLS Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

Related Video: Understanding the Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

Box 0: Ensuring Scene Safety

Particularly for OHCA, it is critical that the provider first ensure that the scene is safe for both the patient and the provider.

Box 1: Identifying Cardiac Arrest and Initiating CPR

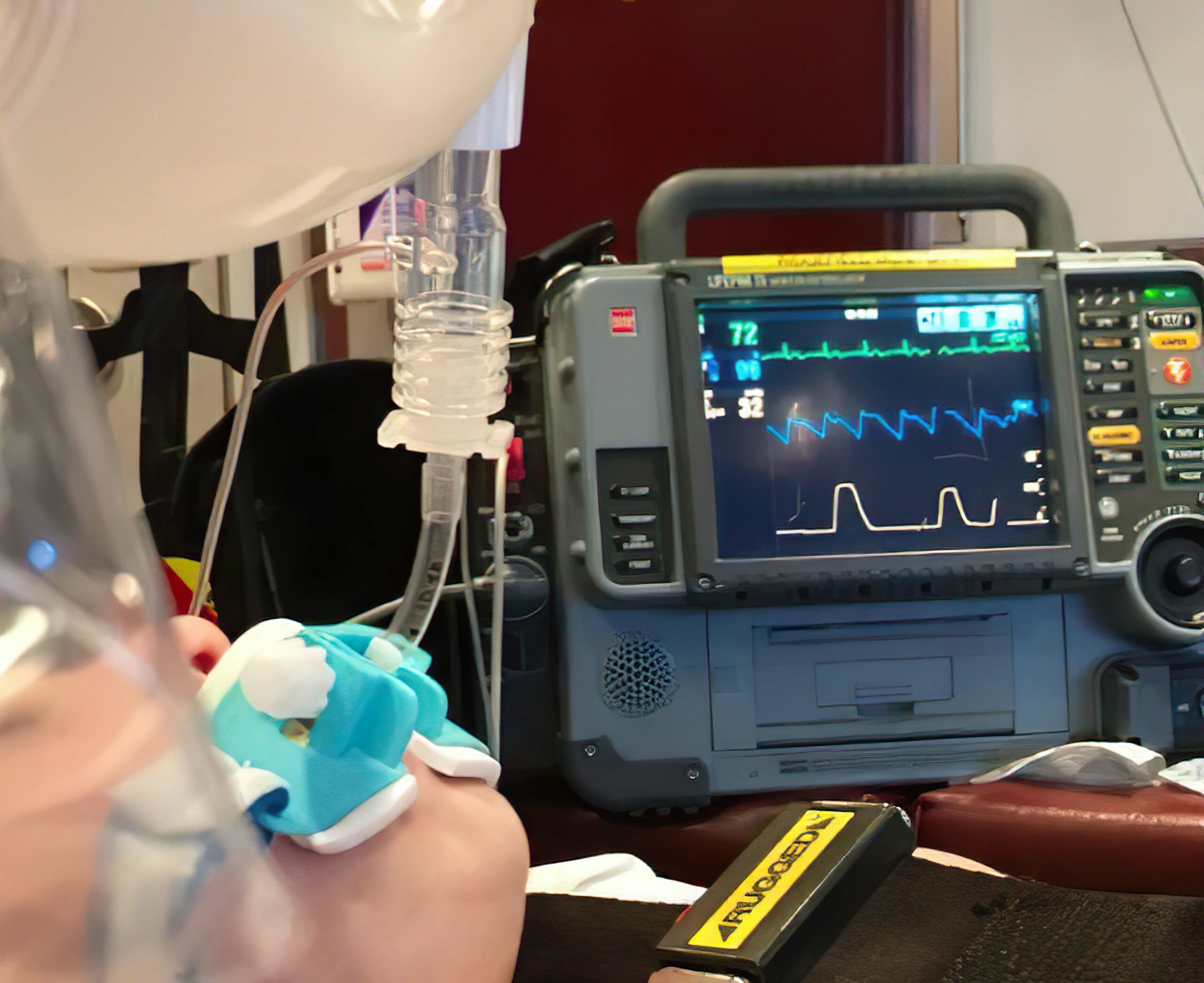

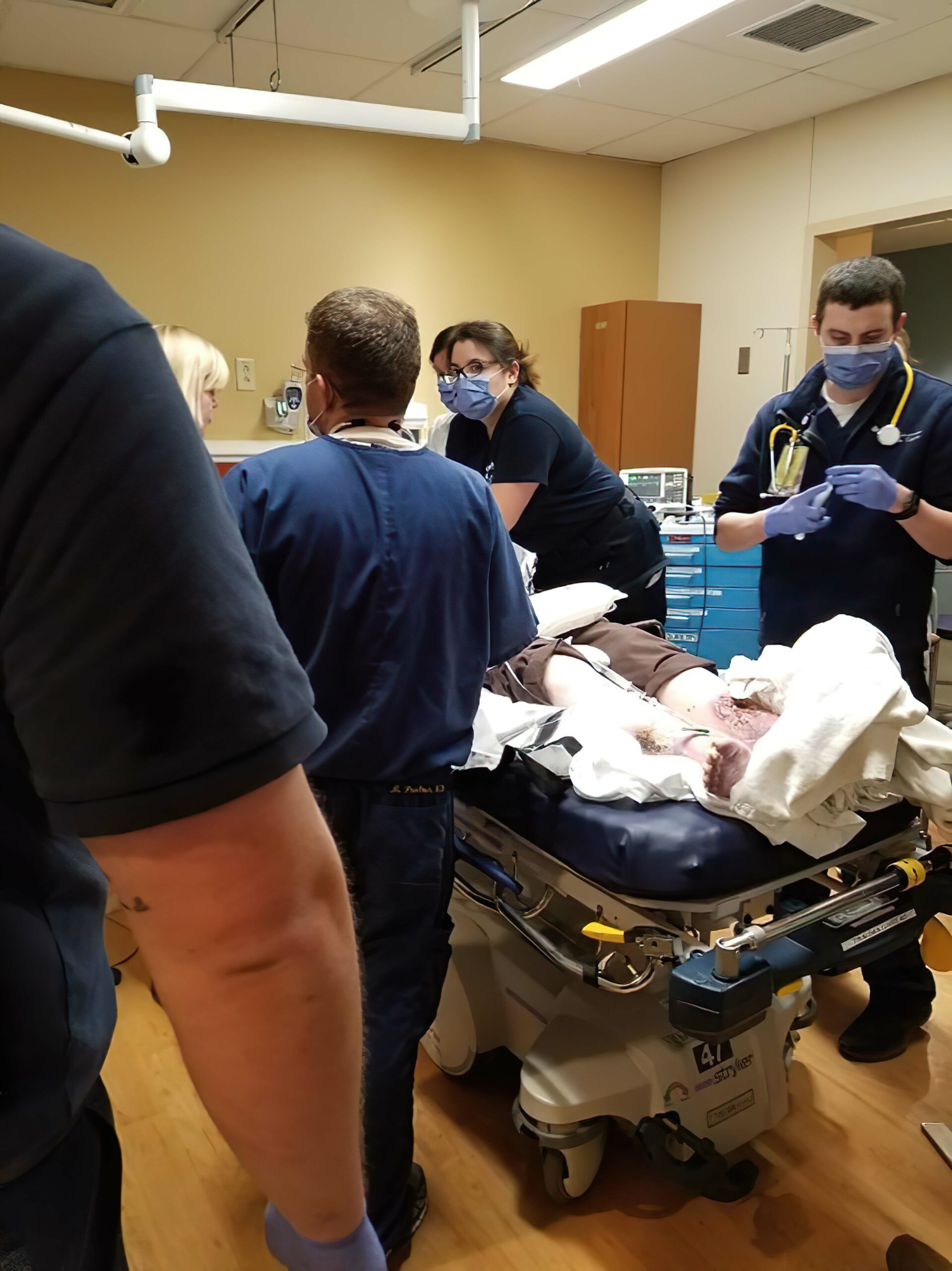

Ideally, the team performs rhythm-based management of cardiac arrest. If there is no pulse, the provider initiates high-quality CPR. If oxygen and a monitor/defibrillator are available, the team attaches those as CPR continues.

Box 2: Identifying Shockable Rhythms

If the rhythm is shockable (VF or pVT), the team proceeds to Box 3. If the rhythm is not shockable (asystole or PEA), they proceed to Box 9.

Ventricular Fibrillation

Related Video: ECG Rhythm Review – Ventricular Fibrillation

Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

Related Video: ECG Rhythm Review – Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (Torsades de Pointes)

Asystole

Related Video: ECG Rhythm Review – Asystole

Pulseless Electrical Activity

Related Video: What is PEA?

Box 3: Administering Shock

When using a manual defibrillator, the first provider performs chest compressions while the defibrillator is charging. Once charged, the provider stops chest compressions, and the second provider instructs everyone to clear the patient. Once everyone is clear of the patient, the second provider delivers a shock at the dosage recommended by the defibrillator manufacturer.

Studies show that biphasic manual defibrillators are preferred over monophasic defibrillators for the treatment of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Biphasic waveform defibrillators set to deliver 200 J or less for the first shock were shown to be efficacious.10

The first dose of shock delivery depends on the manufacturer’s recommended energy dose. If the provider does not know the manufacturer’s recommended dose, the clinician should consider the maximal dose.

The manufacturer’s recommendations should determine the choice between a fixed or escalating energy dose for subsequent shocks.

If the provider does not know this information, escalating energies, or subsequent shocks with a higher energy dose, are recommended. Studies have observed that a fixed energy dose of 150 J with a biphasic defibrillator can terminate initial and recurrent VF with high success rates.11 However, subsequent shocks demonstrated declined shock success.12 The single stacked strategy is preferred over stacked shocks for defibrillation.

Key Takeaway

Energy Dose for Shock

1. First Shock – refer to manufacturer’s recommendation or highest dose available (if the recommended shock dose is unknown)

2. Subsequent Shocks – refer to manufacturer’s recommendations or escalating energies (higher for second and subsequent shocks)

Note: For monophasic defibrillators, the shock dose is a standard 360 J and for subsequent shocks.

Box 4: Continuing High-Quality CPR

The team minimizes CPR interruptions by immediately performing chest compressions after a shock. At this point in the algorithm, it is important to obtain IV or IO (intraosseous) access in anticipation of drug delivery.

Auto-Compression Devices

Auto-Compression Devices

ETCO2 Monitoring

Box 5: Rhythm Check and Shock Administration

After 2 minutes of high-quality CPR, the provider rechecks the patient’s rhythm. If there is continued VF or pVT, the team prepares to administer another shock. The rhythm check should be as brief as possible, and CPR resumed immediately afterward.

Box 6: Epinephrine and Consideration for Advanced Airway

Once the team delivers the shock, they resume high-quality CPR immediately. At this point, two shocks have been delivered, and vascular access is available. High-quality CPR is ongoing.

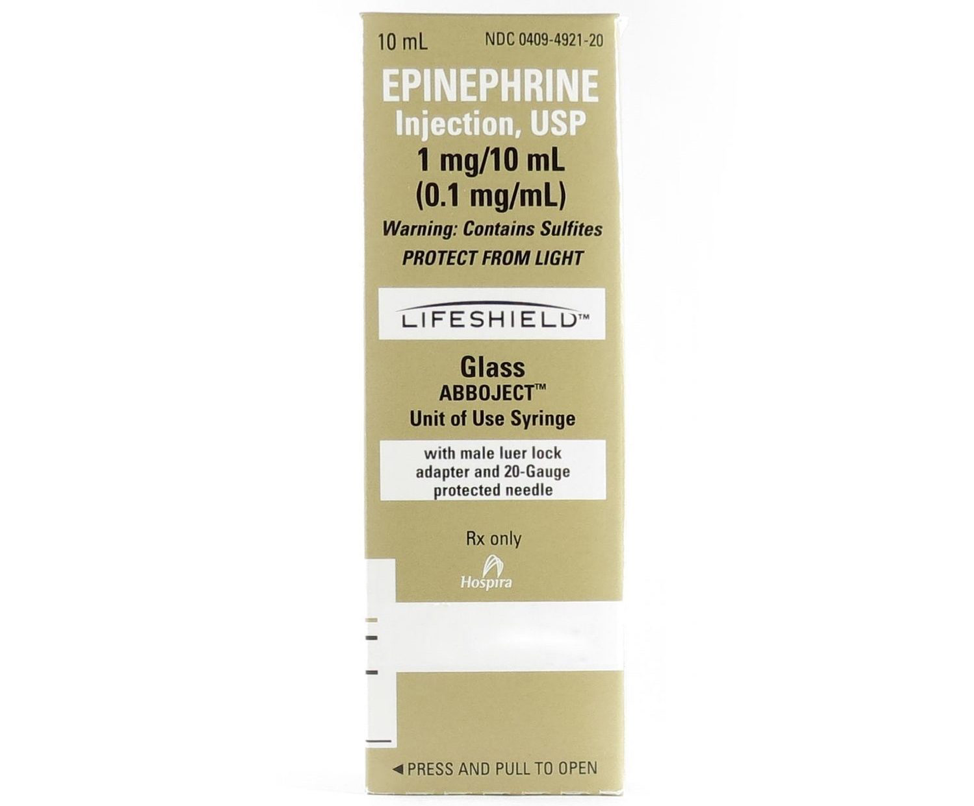

It is now time to utilize drug therapy to restore a perfusing rhythm. The first-line medication for the treatment of VF or pVT is epinephrine.

A cardiac arrest patient may receive epinephrine when feasible after the placement of vascular access. Studies of IHCA patients show an increased chance for ROSC if epinephrine is given within 1 to 3 minutes of cardiac arrest as opposed to after 3 minutes.13

For OHCA patients, studies show increased rates of ROSC if epinephrine is given 9 minutes or less from the onset of cardiac arrest compared with patients given epinephrine later.14

Epinephrine 1:10,000 Box Package Revision

Related Video: Epinephrine – ACLS Drugs

Rescuer Preparing Medication

Administering Epinephrine

The recommendations for treating cardiac arrest are for epinephrine intravenously (preferred) or via the intraosseous route with a preparation of 1:10,000 dilution, 1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes. Studies show that this standard dose is responsible for improved survival and ROSC.15

The addition of vasopressin does not show any advantage over using epinephrine alone. Thus, the AHA no longer recommends vasopressin as a treatment in cardiac arrest.

Key Takeaway

Recommendations no longer suggest vasopressin as a treatment choice in cardiac arrest.

The effects of epinephrine include:

- Vasoconstriction, which causes increased perfusion to the heart and brain

- Increased cardiac output resulting in:

- Increased heart rate

- Increased heart contractility

- Increased conductivity of impulses through the AV node

Related Video: What is Cardiac Output?

Related Video: What is the Cardiac Output Formula?

Considering Advanced Airway

In Box 6, in addition to administering epinephrine, providers are directed to consider the insertion of an advanced airway. This is not always necessary if the patient is being ventilated adequately using a bag-mask.

Ideally, two rescuers are needed to ventilate effectively with a bag-mask. One provider obtains a tight seal with the mask over the patient’s mouth and nose. The second provider delivers each ventilation at the correct time in the CPR sequence (2 breaths are given after 30 compressions) and at sufficient volume to cause the chest to rise but avoiding excessive ventilation. These are essential components of high-quality CPR.

Related Video: Understanding Bag Valve Mask Usage During CPR

Related Video: Tips for Bagging

When it is determined that an advanced airway is needed, there are several essential points the provider must remember:

- Inserting an advanced airway can lead to unacceptable delays in the provision of CPR.

- Only those providers with expertise should attempt insertion of an advanced airway.

- Once inserted, proper placement must be determined by both physical confirmation (equal bilateral chest rise, air entry heard in all lung fields, and no air auscultated over the epigastrium) and physiologic monitoring (waveform capnography).

- The advanced airway is then secured in place, with placement checked frequently to detect any complications, such as dislodgement.

- Once an advanced airway is in place, ventilation and compressions no longer need to be synchronous. The compressor provides continuous chest compressions, while the ventilator provides 1 breath every 6 seconds.

Note: For more information on advanced airways and ventilation during cardiac arrest, see the chapter on adjuncts.

Box 7: Rhythm Check and Shock Administration

Once the initial dose of epinephrine has been given and 2 minutes have passed since the last shock, the team pauses CPR to perform another rhythm check. If the patient’s rhythm is unchanged or refractory (patient remains in VT or pVT), another shock is administered.

Box 8: Administering Antiarrhythmic and Considering Possible Causes

Once the team administers the shock, they should immediately resume CPR for 2 minutes.

Amiodarone is given for VF or pVT refractory to defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy. Lidocaine is an alternative treatment to replace amiodarone. Both drugs are given IV and IO.

Antiarrhythmic Drugs During and Immediately After Cardiac Arrest

Amiodarone is administered for VF or pVT refractory to defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy. Lidocaine is an alternative treatment for amiodarone. Both drugs may be given intravenously and via the intraosseous route.

Key Takeaway

Preparation of Antiarrhythmic Drugs in Cardiac Arrest

1. Amiodarone – First dose 300 mg IV/IO push, then 150 mg IV/IO push for succeeding dose

2. Lidocaine – First dose 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg as IV/IO push, then 0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg IV push for a maximum of 3 doses or a total of 3 mg/kg

Related Video: Amiodarone – ACLS Drugs

Related Video: Lidocaine – ACLS Drugs

Reversible Conditions

The team leader continues to seek and identify possible reversible causes of arrest, including:

- Hypoxia

- Hypovolemia

- Hydrogen ion excess

- Hypo- or hyperkalemia

- Hypothermia

- Tension pneumothorax

- Tamponade, cardiac

- Toxins

- Thrombosis, coronary

- Thrombosis, pulmonary

The Adult Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm

Short Description

This algorithm presents the Cardiac Arrest Algorithm in a circular format to reinforce that cardiac arrest care does not end until ROSC occurs, and Post Cardiac Arrest Care begins.

Algorithm at a Glance

- The circular cardiac arrest care algorithm provides a simple way to understand cardiac arrest care as a continuous process.

- The provider understands that cardiac arrest care involves high-quality CPR, medications, defibrillation, and airway management.

- The provider ensures that post-cardiac arrest care begins at the time of ROSC.

Goals for Cardiac Arrest Circular Care

The provider will recognize that cardiac arrest care is an iterative process that includes:

- Continuous CPR

- Continuous monitoring

- Defibrillation as early as possible

- Drug therapy

- Airway management

- Post-Cardiac Arrest Care

This algorithm was created to present the cardiac arrest patient’s care in a circular algorithm to emphasize the need for ongoing assessment and management.

Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm

Related Video: ACLS Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm

Step 1: Initiating CPR

When a cardiac arrest is suspected, the team begins high-quality CPR, administers oxygen, and attaches a monitor/defibrillator.

Step 2: Interpreting the Rhythm

If VF or pVT, the team defibrillates immediately. If PEA or asystole, the team continues CPR and administers epinephrine early in the process and every 3 to 5 minutes throughout the resuscitation.

Step 3: Step 2 is Repeated after 2 Minutes

The team leader considers an advanced airway and assesses for and treats a reversible cause. The team considers the Hs and Ts to determine reversible causes.

Step 4: The Cycle is Continued until ROSC

Upon return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), the team proceeds to the Post-Cardiac Arrest Care algorithm.

The two shockable rhythms, VF and pVT, do not generate enough cardiac muscle contraction to provide cardiac output. VF is disorganized electric activity, while pVT is organized but inadequate activity of the ventricular muscle. These arrhythmias both require early CPR, defibrillation, ACLS, and post-arrest care.

Related Video: ECG Rhythm Review – Atrial Fibrillation with Rapid Ventricular Response (RVR)

Related Video: ECG Rhythm Review – Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (Torsades de Pointes)

10 Morrison LJ, Henry RM, Ku V, Nolan JP, Morley P, Deakin CD. Single-shock defibrillation success in adult cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2013;84(11):1480–1486. doi: 10.1016/j. resuscitation.2013.07.008

11 Hess EP, Russell JK, Liu PY, White RD. A high peak current 150-J fixed-energy defibrillation protocol treats recurrent ventricular fibrillation (VF) as effectively as initial VF. Resuscitation. 2008;79(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.04.028

12 Koster RW, Walker RG, Chapman FW. Recurrent ventricular fibrillation during advanced life support care of patients with prehospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;78(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.03.231

13 Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Howell MD, et al. Time to administration of epinephrine and outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms: retrospective analysis of large in-hospital data registry. BMJ. 2014;348:g3028.

14 Goto Y, Maeda T, Goto YN. Effects of prehospital epinephrine during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with initial non-shockable rhythm: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17(5):R188.

15 Jacobs IG, Finn JC, Jelinek GA, Oxer HF, Thompson PL. Effect of adrenaline on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2011;82(9):1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.029