Managing Stroke

Managing Stroke

The first step in managing stroke involves identifying it. Patients and the public must be made aware of the signs of stroke so they can react quickly. Following identification, activation of EMS, transfer to the stroke center, and treatment can occur. In patients with ischemia underlying the stroke, there is a limited time window for the treatment of reversible disease.

There are specific guidelines for time to care following arrival at the hospital

- 10 minutes: initial ED assessment and non-contrast head CT ordered

- 25 minutes: neurological assessment and CT completed

- 45 minutes: CT assessment

- 60 minutes (3 hours from symptom onset): fibrinolytics, if appropriate

- 3 hours: admission to a stroke unit.

Related Video: Stroke Assessment and Important Time Frames Outside the Hospital

Stroke Symptoms Illustration

Treatment depends on the individual, family, or bystanders recognizing these signs. If recognition or activation of EMS is delayed by minutes or hours, the patient may no longer be a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy, as it must be given within 3 hours of the onset of symptoms.

Education is key; one research study found that under 10% of stroke patients knew the typical signs of the disease, despite half of them having had a prior stroke or TIA. Additionally, signs may be mild, causing patients to ignore or minimize them. Also, a stroke patient who is alone or asleep may have further difficulties getting expedited care.

Sadly this delay in care affects patients. Only about 3-5% of stroke patients will get rtPA due to time delay.

Step 2: EMS Activation and Care

EMS is vital to identify stroke and transporting patients to the appropriate stroke unit. EMS personnel are vital to the survival chain; despite this, recent data indicates that only 14-32% of patients contacting EMD arrive at the stroke unit in under 2 hours from onset of symptoms. Appropriate EMS management can decrease the time to hospital assessment and management. The role of EMS in stroke care includes:

- Rapidly identifying likely stroke patients

- Supporting vitals

- Communicating with ED about the patient

- Rapidly transporting the patient to the ED

When the patient or family members call EMS, the staff are usually able to identify stroke over the phone half of the time. There may be a benefit of adding scripted questions to help improve diagnostic accuracy. This allows rapid activation of EMS to the patient’s side for transport, similar to cases of trauma or acute MI.

Following rapid assessment, including basic life support, EMS staff should obtain a history and assessment to identify the likelihood of stroke. Vital to this is the time at which the symptoms first started. This will be key in determining the patient’s treatment, as this will be the time from which the three-hour time frame for rtPA will begin. Other important aspects of history include recent medical history, prior history of stroke or TIA, as well as ACS and atrial fibrillation. Also important to note are any bleeding disorders, comorbid illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes, recent trauma or surgery, and the use of anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs.

Stroke Scale for Detection

EMS can also use scales developed to detect a stroke. Scales include the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scales (CPSS), Los Angels Prehospital Stroke Screens (LAPSS). Both have good sensitivity as well as specificity for identifying ischemic stroke. The CPSS can be done in under one minute and looks for three abnormal findings:

- Face droop

- Arm drift

- Speech abnormalities.

Determining appropriate hospital

If the patient appears to have a stroke, immediate transport to an appropriate hospital is key. EMS must communicate transport to the hospital to expedite care. It is beneficial for EMS to go past a hospital without stroke care capabilities as this can further delay care, and research indicates that this leads to worse outcomes at a year with worse survival, neurologic deficits, and quality of life. An option, if available, is air transport; however, studies looking at the benefit are minimal. This may be particularly helpful in rural counties to allow rapid transport to an appropriate hospital.

Immediate transport to an appropriate hospital is paramount for stroke patients.

Facial Droop

Pronator Drift

EMS management

The EMS can provide care as long as it does not delay transport. This includes obtaining IV access and providing IV normal saline. Typically, hyperglycemic fluids should not be given unless the patient has known hypoglycemia. EMS can obtain a finger stick for glucose, as well as begin cardiac monitoring and possible 12 lead ECG if there are any associated ACS symptoms. EMS should provide supplemental oxygen if the O2 saturation is under 94% or unknown, as hypoxemia can worsen ischemia and neurologic damage.

Managing Stroke in the ED

Step 3: Assessing and stabilizing in the ED

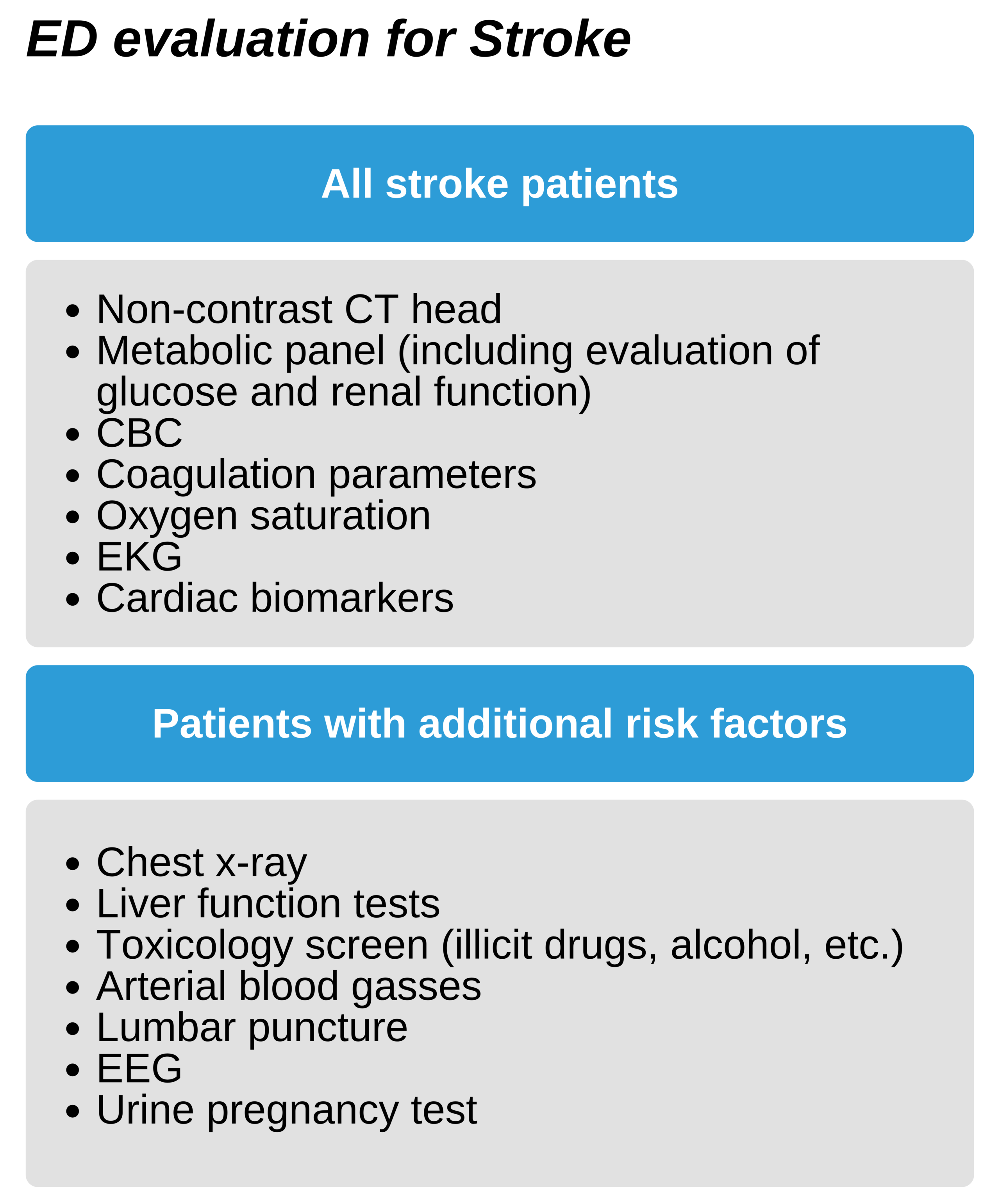

After arrival at the ED, there should be a rapid assessment of the potential stroke patient in under 10 minutes. This includes a neurologic assessment, ordering a non-contrast CT of the head, and alerting the stroke consult team or neurologist. Additionally, support of the patient’s vitals (the ABC’s) is key during this time. Patients with hypoxemia (oxygen saturation below 94%) should receive supplemental oxygen. IV access should be obtained if not done during transport for laboratory work, including coagulation parameters, complete blood count, and electrolytes. Hypoglycemia, if present, must be treated at once as this can mimic a stroke. Place the patient on cardiac monitoring for the first 24 hours after admission to rule out atrial fibrillation as well as other complicating arrhythmias.

Evaluation should include ruling out other etiologies on the differential, especially those that can be misinterpreted as stroke or common comorbidities.

Key Takeaway

Priorities for ED management

- Determining if stroke is the underlying etiology

- Establishing time of onset of symptoms

- Triaging ischemic vs hemorrhagic etiologies

- Providing rtPA if appropriate

Determine the onset of symptoms

While EMS should ask the time on the onset of symptoms, both the patient or family members may be unsure of the exact time. Ask them to relate it to other events that can be timed, such as a TV program or another person’s arrival. In patients who were alone or asleep, the onset of symptoms will be the last time another individual saw them acting normally.

Key Takeaway

Head CT takes priority as this will guide decision for fibrinolysis.

Do not delay CT unless:

- The patient has a high risk of bleeding diathesis

- The patient is currently on anticoagulants or heparin

- Anticoagulant use is unknown

Neurological stroke assessment

There are 5 important areas to assess:

- Time of symptom onset

- Consciousness level

- Stroke severity

- Ischemic or hemorrhagic etiology

- The vascular territory of stroke (anterior or posterior)

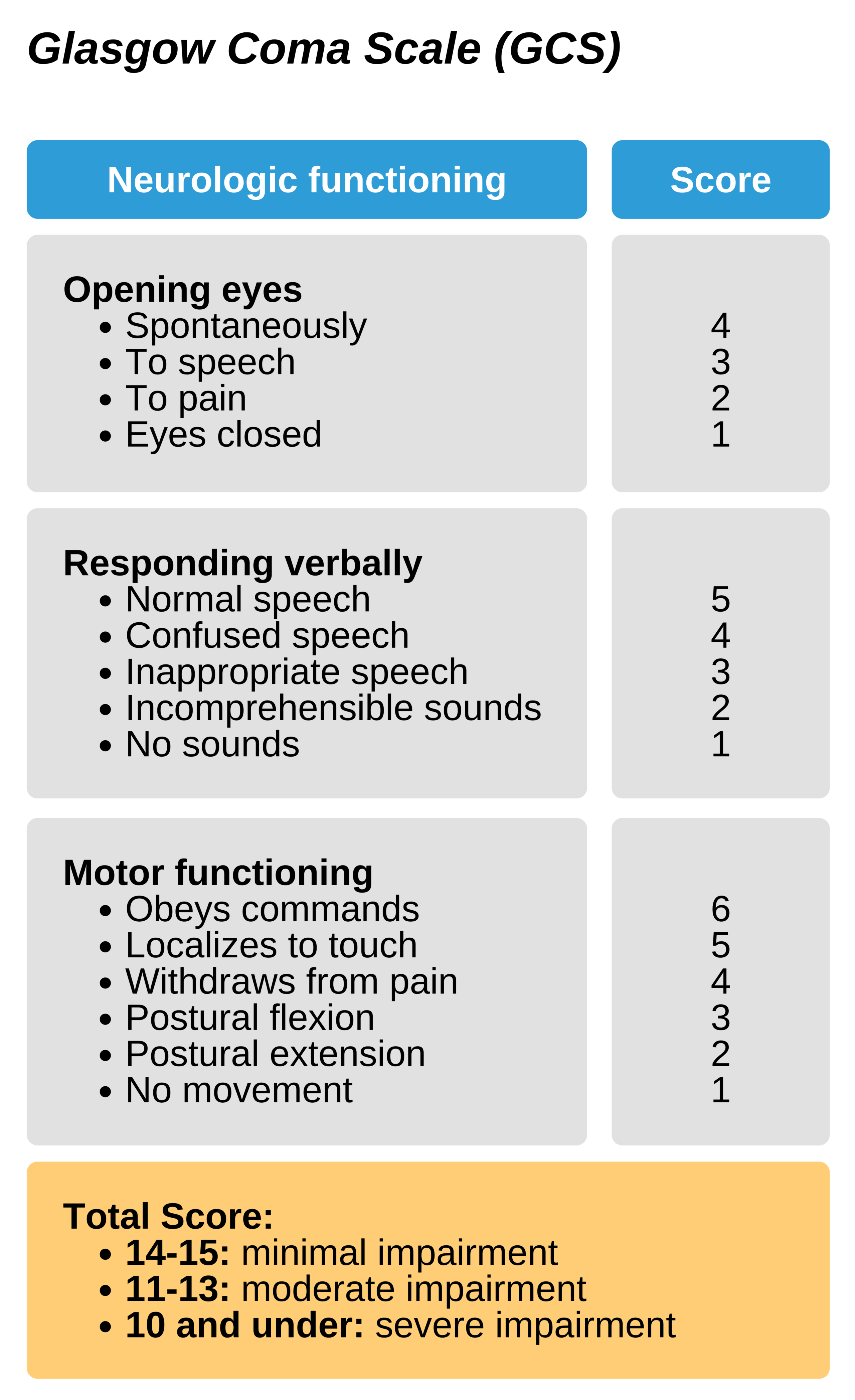

Assessing consciousness

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a well-established method to assess the patient’s consciousness and can allow reassessment over time. IT is scaled from 3-15 and evaluates three signs of neurologic function: opening the eyes, responding verbally, and motor functioning. GCS of 3 indicates a non-responsive patient, and a score of 8 or below indicates a poor prognosis.

Step 4: Stroke Team Assessment

Assessment of neurologic function should take place in under 25 minutes from ED admission and should evaluation of the history of illness and the time of symptom onset. Bystanders, family members, or EMS may be vital in this assessment. Complete a neurologic assessment using a stroke scale.

Key Takeaway

Determine when “last known normal”

The time since the onset of symptoms is vital for management with rtPA. If it is not known, the patient cannot receive rtPA.

Speak with bystanders or family members to get this information.

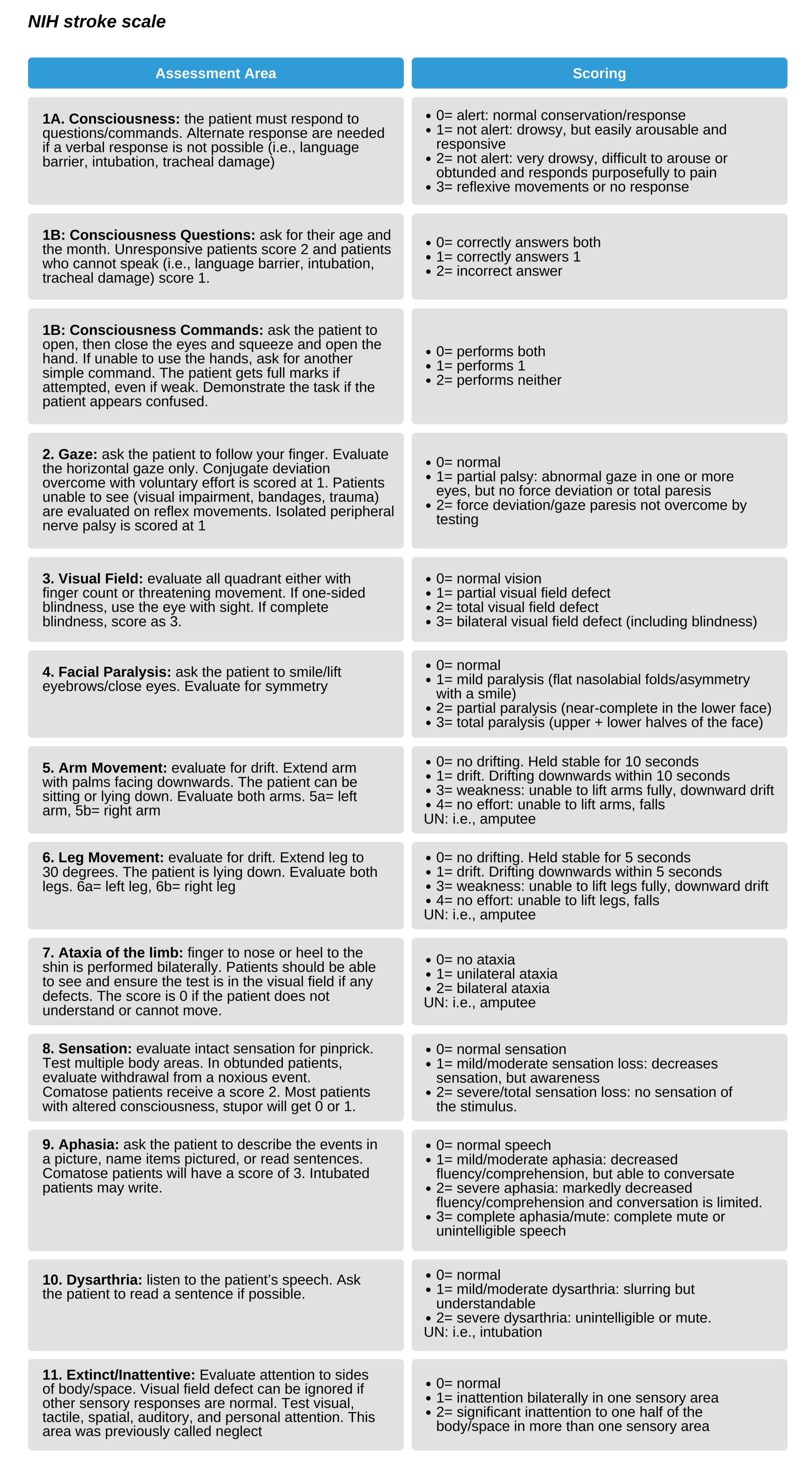

Stroke Severity

Use the National Institute of Health (NIH) stroke scale to determine the severity of the stroke. This 15 area scale is widely used and has been validated to correlate with a more complete neurologic evaluation. The test can be completed by physicians and non-physician stroke specialists. It is highly correlated with outcomes over the long-term and allows standardization of patient’s baseline functioning. Typically the test takes under 7 minutes to complete.

The NIH score is between 0-42, with 0 being normal. It evaluates consciousness, vision and eye movements, sensation, language, and motor and cerebellar functioning. A score below 4-5 usually indicates only minor defects; however, disabling deficits in one area of testing (i.e., severe aphasia or visual field defect) may have a low score. In this case, this patient may benefit from fibrinolysis if they are within the 3-hour time frame. Additionally, patients with significant ischemia who show some improvement but maintain significant deficits may benefit from fibrinolysis.

A score above 22 suggests a large ischemic area, and these patients are at risk for intracranial hemorrhage. These patients and family members should be counseled regarding the significant risk of hemorrhage associated with fibrinolysis. The decision to proceed is based on careful evaluation of the risk and benefits in the individual case.

Managing Hypertension

There are certain unknowns regarding the acute treatment of hypertension in stroke. If the patient is a candidate for fibrinolysis, blood pressure should be controlled with a goal systolic BO of under 185mm Hg and a diastolic BP of under 110 mm Hg. If the patient is not able to meet these goals in the fibrinolytic time frame, then they lose the chance for this intervention.

Patients with significant hypertension- a systolic BP over 220 mm Hg or a diastolic BP over 120 mm Hg- may benefit from the treatment of hypertension even if they cannot receive rtPA. This may benefit comorbid illnesses such as heart failure, acute MI, or aortic dissection. A reasonable goal is to decrease BP between 15-25 % in the first 24 hours.

Some options for management of hypertensive patients (BP over 185/110) who are candidates for reperfusion include:

- 10-20 mg IV labetalol for 1-2 min. Repeat once if needed

- 5mg/h IV nicardipine. Increase if needed 2.5mg/h each 5-15 minutes to max of 15 mg/h.

- Other options include enalaprilat or hydralazine if appropriate

Patients become ineligible if BP does not remain under 185/110.

Following administration of rtPA/acute reperfusion, monitor BP at 15-minute intervals in the first 2 hours, 30-minute intervals for the following 6 hours, and 1-hour intervals for the following 16 hours. If systolic BP 180-23 mm Hg or if diastolic BP 105-120 mm Hg, manage with:

- 10 mg IV labetalol, then 2-8 mg/min infusion

- 5mg IV nicardipine. Increase if needed 2.5mg/h each 5-15 minutes to max of 15 mg/h.

- Consider sodium nitroprusside BP unable to be controlled or diastolic BP over 140 mm Hg

Brain imaging

Typically, the imaging of choice for stroke is a non-contrast CT. This test can diagnose hemorrhagic strokes and rule out other etiologies mimicking an acute stroke, such as a brain mass. Some stroke facilities will use MRI scans that have near similar efficacy. Additionally, there is research evaluating the use of CT and MRI angiography, as well as multimodal and perfusion CTs. Currently, CT without contrast is the standard of care, and other unproven technologies should not delay this imaging.

A CT scan is the brain imaging of choice for stroke patients.

Obtain this emergency CT by 25 minutes after admission and ensure it is interpreted by a skilled physician by 45 minutes. It is important to note that ischemia may not be seen on CT within the first few hours of the stroke; however, the study is still key to triaging patients since:

- Lack of hemorrhage may make the patient a candidate for fibrinolysis

- The finding of hemorrhage excludes the patient from receiving fibrinolysis. Neurology should be consulted for further management.

- In patients ineligible for fibrinolysis with no evidence of hemorrhage, provide treatment with aspirin, and admit the patient to the stroke unit.

On the non-contrast CT, hemorrhage appears 3% denser than brain tissue. Additionally, CT can differentiate between free blood, hemorrhage, and tissue. No contrast is used because contrast material will light up similarly to free blood. Additionally, other complications such as edema, mass effects, and midline shift will be seen on CT. Typically, in the first hours after an ischemic stroke, the non-contrast CT may be normal. Changes indicating blood flow are unlikely to develop in the first three hours. If there is a low density are on initial CT, this suggests that the onset of symptoms was at least 6-12 hours earlier, as this is how long it takes for these signs to show up on CT. Rarely large infarcts will be seen on CT early. Typically, findings are quite subtle such as a loss of distinction between the gray and white matter, hypodensity, or sulcal effacement.

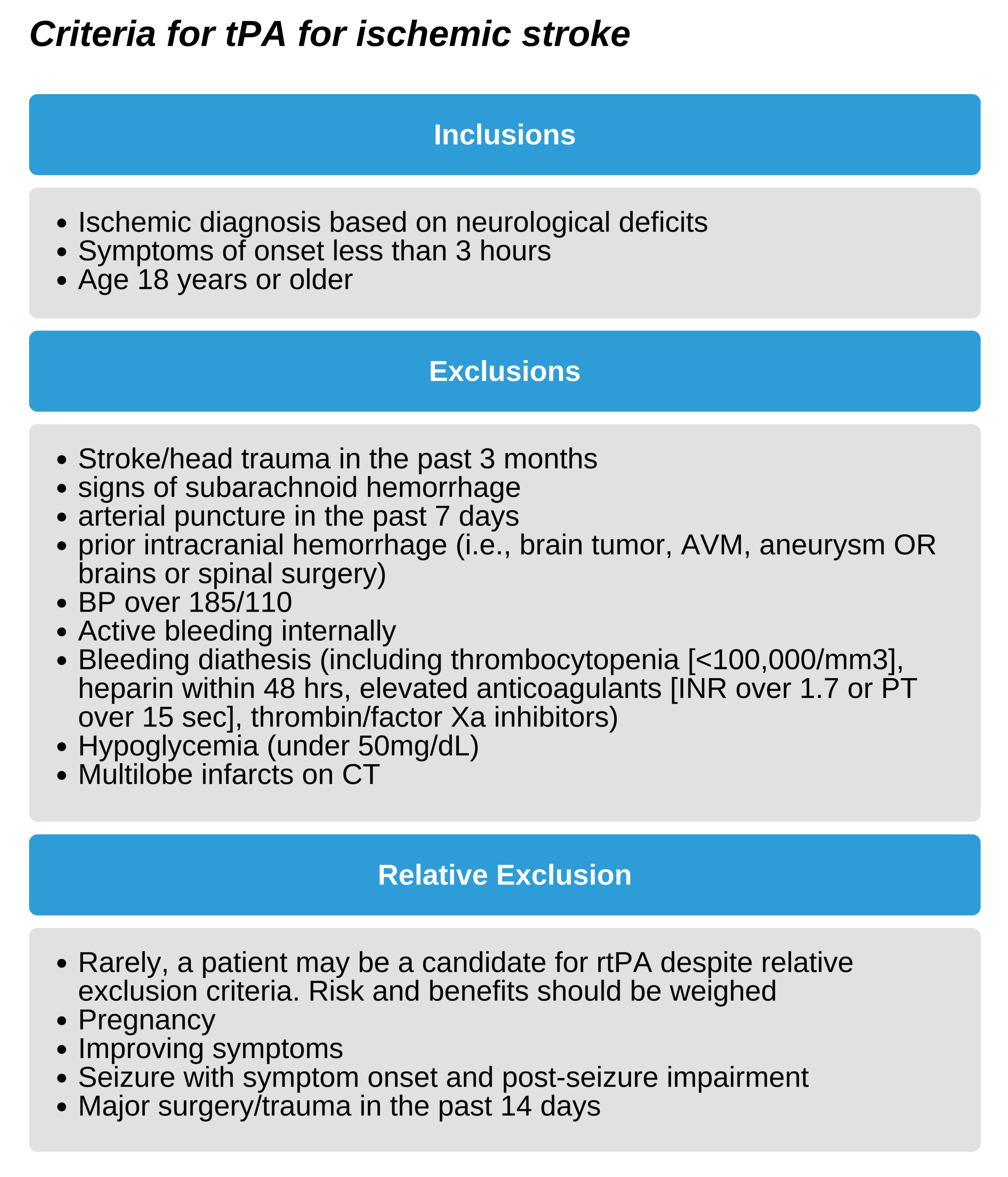

Deciding to Administer rtPA

If the CT is negative, acute stroke form ischemia is likely. The checklist for fibrinolysis should be used, and a follow-up neurologic evaluation (i.e., NIH stroke scale) should be done. If the patient’s symptoms are markedly improved or resolved, rtPA should not be given.

Patients who have a normal CT are candidates for fibrinolysis if there are no other contraindications

Key Takeaway

A normal CT indicates fibrinolysis if no contraindications.

rtPA benefits

Studies show that rtPA improves neurologic function when given in the 3-hour time frame. It is important to note that this benefit is when the fibrinolytic criteria are followed in a stroke center with competent physicians. Benefits persist to a year of follow-up and are maintained even with a range of stroke severities.

rtPA risks

The provider must remember that rtPA has negative effects, and the exclusion criteria should be ruled out to help limit risks. The major risk is of bleeding intracranially, and it occurs in between 4.6-6.4% of patients. The risk is about 10 times the risk of not receiving rtPA. However, the mortality overall is not increased. Other possible complications include hypotension, extracranial bleeding, especially at a puncture site, and angioedema of the mouth and tongue.

Maximizing Success

rtPA administration is best when meeting the eligibility requirements in a stroke center with competent healthcare providers. The positive outcomes may not carry over in hospitals without a stroke center that does not adhere to the strict guidelines. However, this does not mean that smaller hospitals cannot replicate the results. Rather, following strict eligibility and exclusion criteria, access to experienced healthcare providers, and continuous feedback can help improve results in these facilities as well. In this effort, the Brain Attack Coalitions determined criteria for stroke centers. Primary stroke centers can manage numerous patients with uncomplicated strokes.

In contrast, comprehensive centers can manage patients with complicated strokes who may require advanced care, including surgery and stroke ICUs. Recommendations include:

- EMS transport to hospitals with the stroke center designation;

- Development of primary and comprehensive stroke centers;

- External certification for stroke centers.

Final checks before administering fibrinolytics

Ensure CT is negative for signs of hemorrhage or non-acute stroke

- Even a small bleed can lead to fatal bleeding if rtPA is given;

- Obviously decreased densities on CT indicate stroke over 3 hours old;

- Signs of a large infarct are a relative contraindication as large infarcts are associated with the risk of bleeding. However, due to the poor prognosis in these patients, individual evaluation for risks and benefits should be completed.

Reevaluate neurologic status

If the neurologic exam is improving rapidly or has resolved, the risks of rtPA may not be justified. These patients may have a complete reversal or partial obstruction that would not be improved by rtPA. However, if the patient has significant deficits, despite a low score on the NIH stroke scale, rtPA may be of benefit

Ensure no exclusion criteria

Double-check that the patient is not excluded from receiving rtPA. This should be done by the physician who will make the final decision to administer rtPA and must be documented in the patient chart.

Ensure within the time frame

The patient must get rtPA within 3 hours from the onset of symptoms. The physician, again, should double-check this and document interval to rtPA in the chart.

Administering rtPA

In patients who meet criteria for rtPA long-term outcomes are improved. While the time limit is 3 hours from onset of symptoms, the goal should be to administer the medication within one hour of hospital admission. A dose of 0.9mg/kg (mas of 90 mg) is given over 60 minutes, with 1/10 given as a bolus. During administration:

- Monitor the patient’s neurologic signs; obtain a stat CY if this deteriorates

- Monitor vitals and provide antihypertensive medications if systolic BP between 180-230 mm Hg or diastolic BP between 105-120 mmHg

- Patients should be managed in a stroke unit or ICU as they will require careful post rtPA assessments.

- Do not give antiplatelets or anticoagulants in the following 24 hours after rtPA administration

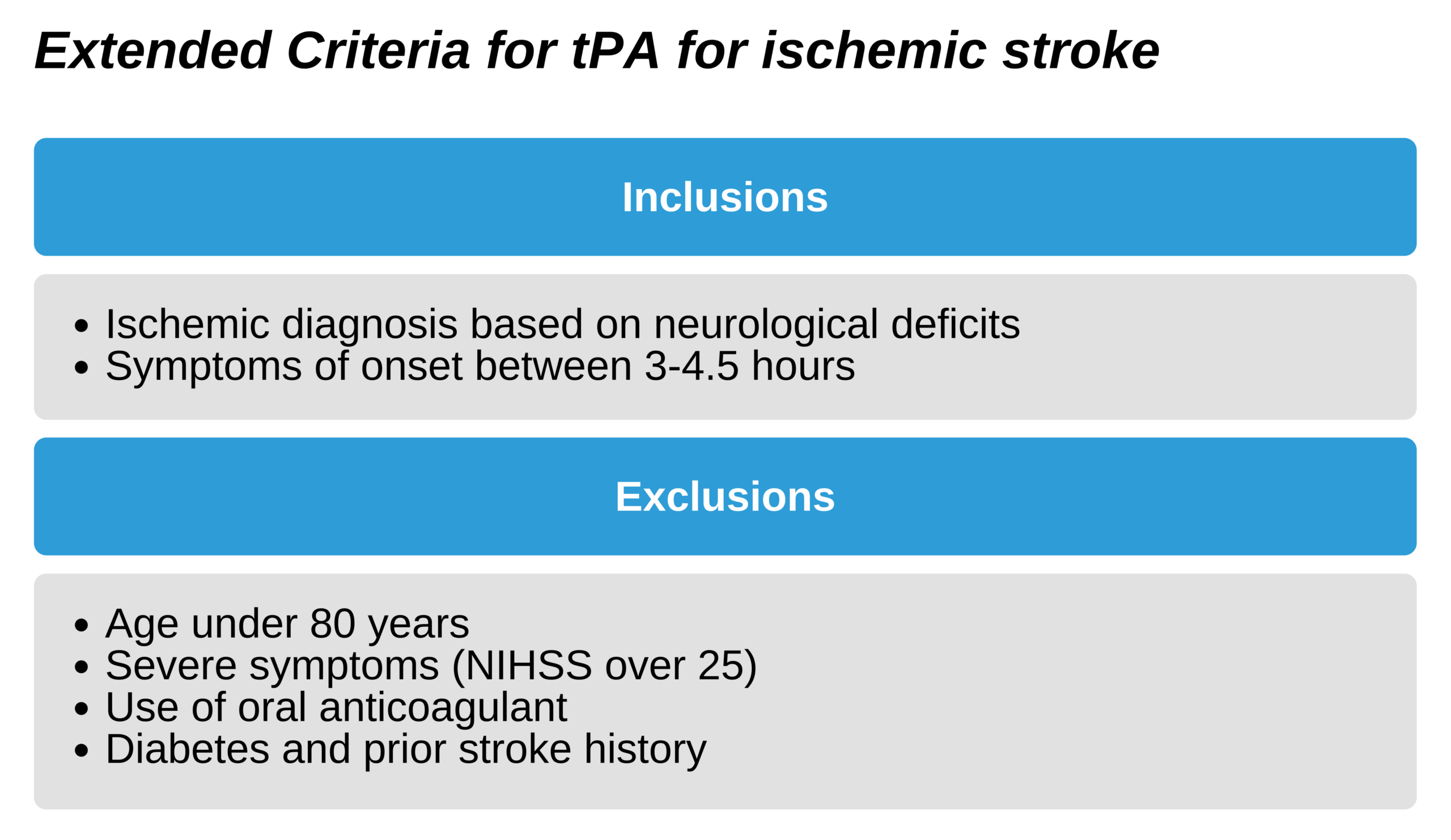

The extended criteria, allowing rtPA at up to 4.5 hours following the onset of symptoms, is associated with clinical benefit, but less than that of the 3-hour time frame. It is not currently endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US but has been approved by the AHA and ASA. This extended protocol should only take place in a setting in which criteria are adhered to via protocol, and skilled clinicians are adept at stroke management.

Key Takeaway

Do not give heparin in the initial 24 hours following rtPA

Never give aspirin if there is evidence of intracranial hemorrhage

Aspirin can be given in stroke patients who do not meet criteria for rtPA

Endovascular interventions for Stroke

Endovascular intervention is an alternative (second-line) management for acute stroke. It is usually used in selected patients who meet strict criteria. A benefit of endovascular interventions is that the time window is extended to 6 hours from symptom onset.

Cerebral rtPA

rtPA can be administered through cerebral arteries. In patients who do not meet the standard criteria for rtPA, intra-arterial administration might be an option. This treatment must be done in centers with expertise in its administration. The FDA has not approved its use

Mechanical Intervention

Mechanical intervention includes disruption of the clot and retrieval of the clot using a stent. It is of benefit to selected stroke patients. The following inclusion criteria must be met:

- Rankin scale of 0-1

- Met extended (under 4.5 hours) inclusion criteria for rtPA and received the medication

- Obstruction in internal carotid or proximal middle cerebral arteries

- 18 years of age or more

- NIH score = 6 or above

- Alberta Stroke CT Score = 6 or above

- Treatment commenced at under 6 hours from onset of symptoms

Patients who meet the criteria should be evaluated for treatment. This can be given in addition to rtPA. Rapid transport is needed to meet time restraints.

Post-stroke Care

Following acute treatment, patients should be transferred to a stroke unit or other intensive care unit. Patients will need repeated and frequent neurological assessment and supportive management. If there is a change in clinical status, a stat CT is required to rule out worsening edema or post-treatment hemorrhage.

Patients will also require IV fluid support to maintain volume, management of airway, and support of nutrition. There is a risk of seizures following a stroke, and patients should be monitored. While prophylaxis is not standard, rapid treatment is warranted with prophylaxis for those who have seizures. Control the blood pressure and monitor the patient for signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Hyperglycemia

Stroke can be complicated by hyperglycemia in about 1/3 of patients. This finding worsens outcomes, although treatment is not necessarily correlated with improved outcomes. Due to the benefit of hyperglycemic control in other acute conditions, however, treatment is usually rendered. AHA and ASA recommend insulin therapy if glucose is over 185 mg/dL.

Temperature Regulation

Hyperthermia is associated with worsened neurologic function in stroke patients. While decreasing temperature has not been shown to improve outcomes, hyperthermia above 37.5 degrees C is usually managed. Additionally, assess for and manage any additional sources for fever. Hypothermia induction can protect the brain following stroke. Improvement in patients with cardiac arrest flowing hypothermia induction is the impetus for this treatment. Hypothermia is thought to be safe, based on small animal studies when the temperature is lowered between 33 and 36 degrees C. Temperatures lower than this may cause adverse events, including arrhythmias, pneumonia, cardiac failure, hypotension, and increasing intracranial pressures at rewarming. Since there is no good human data, it is unclear if this should be routinely used in stroke patients.

Dysphagia Evaluation

Following a stroke, patients must have a swallow screen to ensure they can safely take water, food, or medications by mouth. A simple evaluation consists of asking the patient to take a sip of water. If this is done without problems, a large gulp can be tried. If the patient has no complaints after 30 seconds, then the patient is safe to take thickened fluids. The patient will still require formal speech pathology evaluation. If the patient fails, medications must be given rectally or via IV.