NSTEMI

While the pathology for STEMI and NSTEMI is the same, these groups of patients have different treatment plans. After ruling out other significant or life-threatening conditions, the diagnosis is made utilizing patient history and the ECG. At this time, patients are categorized into specific management strategies and treated accordingly while continuing to assess.

ACS-type chest pain

When evaluating chest pain, healthcare responders must obtain a focused history and physical exam to rule in ACS and rule out other disease states. There is no one specific finding that will accomplish this goal. Instead, responders use their clinical insight to make the diagnosis.

During the primary assessment, it is important to stratify the patient’s risk for ACS while paying continued careful attention to signs or symptoms suggesting the underlying disease process. In this way, the final diagnosis is reached.

Stable angina is predictable, while unstable angina is not.

Acute and life-endangering etiologies of chest pain include:

- ACS

- tension pneumothorax

- pulmonary embolism

- cardiac tamponade

- aortic dissection

Defining Unstable and Stable Angina

Stable angina refers to chest pain worsened by exercise or stress and improved with rest and nitroglycerin. This is a predictable response, and patients often will know the amount of activity that will cause their symptom and how much rest or medication will relieve it.

Key Takeaway

The following changes over 1–2 days suggest unstable angina that can progress to major adverse events:

- Increased frequency/severity

- Lowered threshold of activity

- Symptoms at rest or causing nighttime awakenings

On the other hand, unstable angina refers to a sudden episode of cardiac ischemia that can progress to infarct or myocyte death. Symptoms may progress over hours to days with progressive worsening. These patients have an increased chance of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), including death, acute MI, and the need for reperfusion strategies.

Typically, patients with unstable angina will have an underlying unstable plaque that causes symptoms. These patients are differentiated from other ACS syndromes due to a lack of specific ST changes and normal cardiac markers.

There are three categories:

- Resting angina: occurs with rest, and lasts usually < 20 minutes

- Nighttime angina: leads to nighttime awakenings

- Acceleration angina: progression with increased frequency, duration, or reduced threshold for the inciting activity level

Neither type of angina causes irreversible damage to heart muscle. However, if the low blood flow states are prolonged, myocytes can die and cause necrosis. This necrosis causes a rise in cardiac markers (i.e.g, CK-MB and troponins), which usually can be detected after at least 20-30 minutes. When infarct occurs, the typical ECG changes may be seen, and elevated biomarkers and patient symptoms will confirm the diagnosis.

Angina is classified into four classes based on severity

- Class I: angina is caused by strenuous or prolonged physical activity

- Class II: angina is caused by moderate activity such as rapidly climbing stairs, uphill walking or walking in non-temperate conditions (cold/wind)

- Class III: angina is caused by limited activity such as walking 1-2 blocks or a flight of stairs at a normal pace

- Class IV: angina is caused by any activity

Suggestive Symptoms

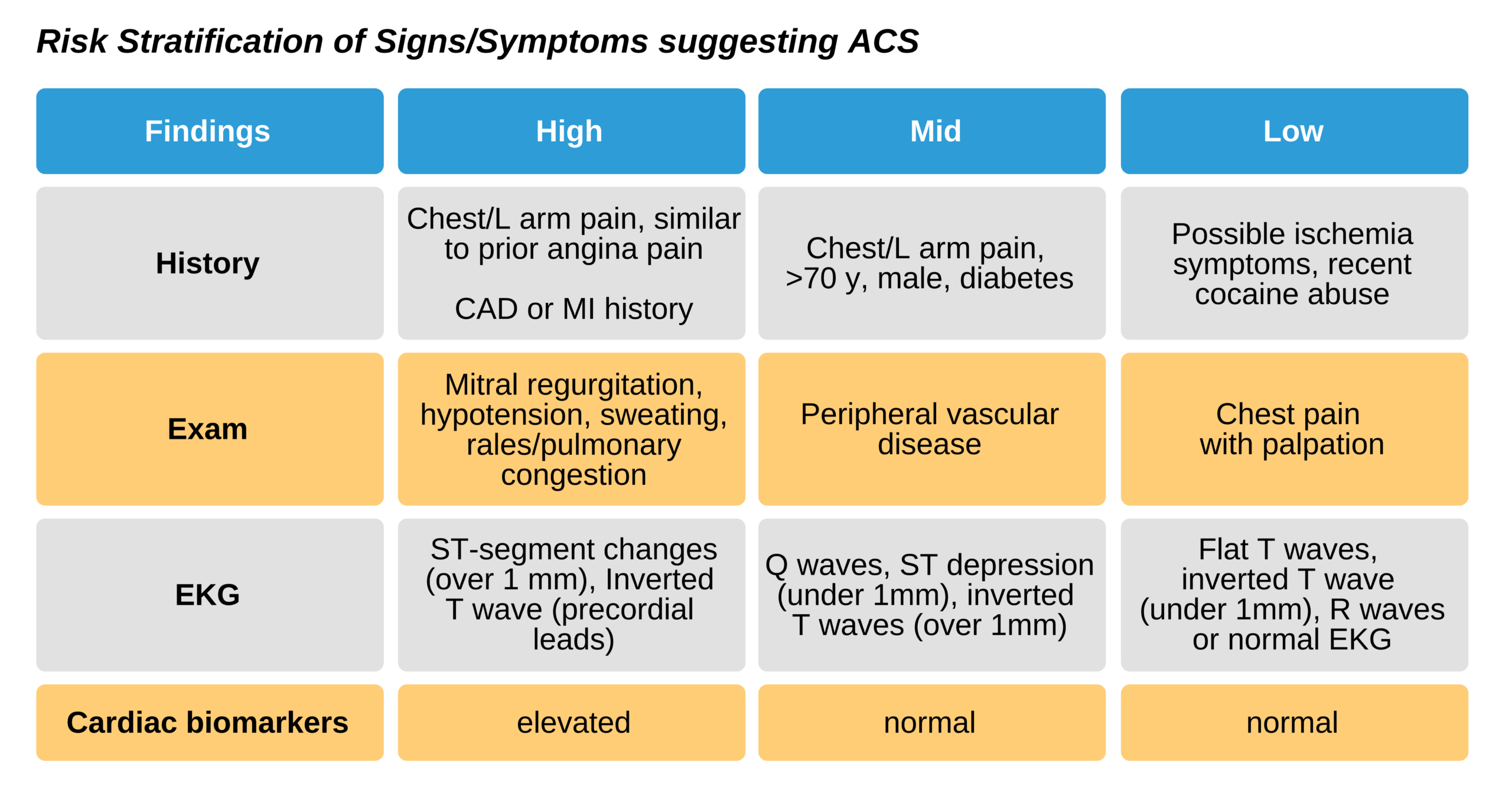

While the majority (about 75%) of patients will have chest pain with ACS, some patients may have no or atypical symptoms. Patients with no ECG evidence of STEMI can be grouped into 3 classes that stratify their risk of ACS. Patients in the highest risk group will have typical ACS chest or left arm pain that reproduces past angina pain. The next group has specific risk factors, including age above 70, male gender, and diabetes. Other risk-stratifying conditions include a history of coronary artery disease, findings of left ventricle dysfunction, the severity of ECG changes, or cardiovascular disease as well as arterial bruits.

Diagnosing patients who do not have typical symptoms is more difficult; however, using these guidelines can help improve the process. Additionally, a high index of suspicion in groups who commonly have atypical symptoms can help. These groups include the elderly, diabetics, and women who may not have chest pain radiating to the left arm. Interestingly, many men do not have these classic findings. These findings are not sensitive for ACS, and patients without them may have significant disease. About 54% of those with typical ACS symptoms have ischemic disease, while those who have ischemic disease, 42% complain of indigestion or burning. Nearly as many could not accurately describe their symptoms and as many as 12% had pleuritic symptoms.

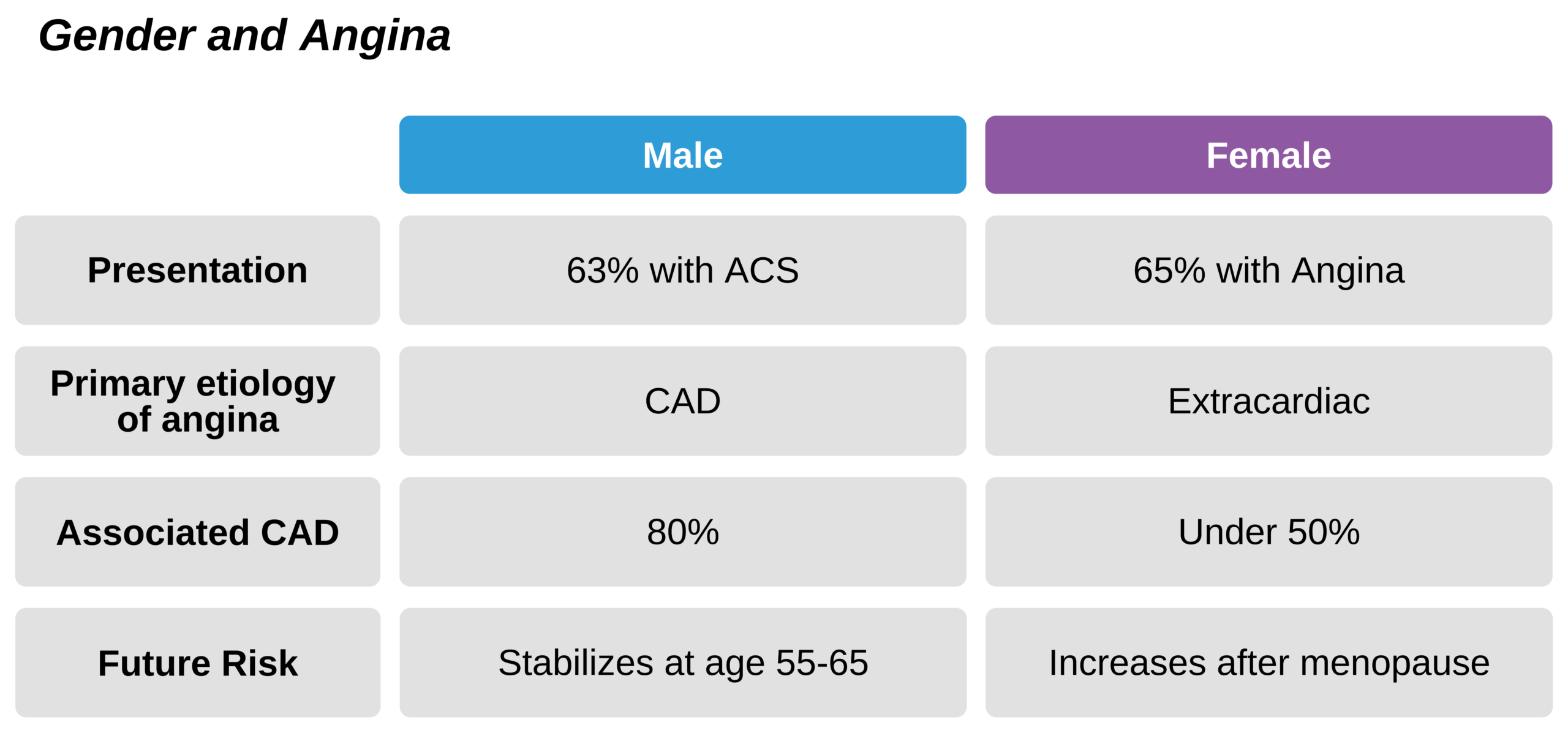

Women

Women often present later than men, partially due to the higher likelihood of atypical symptoms. Younger women before the age of menopause have a lower risk for CAD but do present with classic angina. Women are less likely to have a diagnostic angiogram. Consequently, they are incorrectly thought to have non-ischemic chest pain. It is also thought that women have better outcomes than men. This is inaccurate as women have similar prognoses but actually may have worse outcomes and long-term disability. Common atypical presenting symptoms for women include:

- Nighttime or resting angina.

- Angina with mental or emotional stress

- Dyspnea, palpitations, sweating, nausea, fatigue

- Atypical angina (i.e., non-central chest pain that is not reproducible with exertion or improved with rest)

Diabetes

Patients with diabetes may not have chest pain but rather complain of fatigue or weakness. Other symptoms may include dyspnea, lightheadedness, or fainting. These atypical symptoms may be due to diabetic neuropathy and impaired bodily sensations.

Equivalents of Angina

Some ACS patients present with angina equivalents rather than chest pain. Rather than have atypical symptoms, they do not really get chest pain but rather have alternative symptoms. This is more common in people with diabetes and elderly patients and can be a result of impaired left ventricle function or myocyte instability due to ischemia. Equivalents include

- Dyspnea at rest or on exertion (indicates left ventricular dysfunction)

- Palpitations, syncope, exertional syncope, and near syncope (indicates ischemia associated arrhythmia)

Signs of these equivalents are pulmonary edema and congestion, an enlarged heart, and the 3rd heart sound. Patients can also develop ventricular arrhythmias such as sustained and non-sustained VT, ventricular ectopic beats, and VF. Additionally, ventricular ectopy worsened with activity also suggests ischemia. It is rare for atrial fibrillation to be a presenting sign. Typically, these angina equivalents are only identified in hindsight when ischemia has been diagnosed.