High-Quality Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

The principles of Basic Life Support (BLS) and AED use were reviewed in Chapter 2. In 2010, the American Heart Association shifted away from the A-B-C (airway, breathing, compressions) sequence to C-A-B (compressions-airway-breathing).20 However, since respiratory failure is the most frequent cause of cardiac arrest in children, attention to ventilation is an integral part of pediatric resuscitation.

Although compressions come first in the sequence C-A-B sequence, addressing airway and breathing is no less important. The exception is lay rescuers, who can be readily coached to perform compression-only CPR and who may waste valuable time attempting to provide rescue breaths.

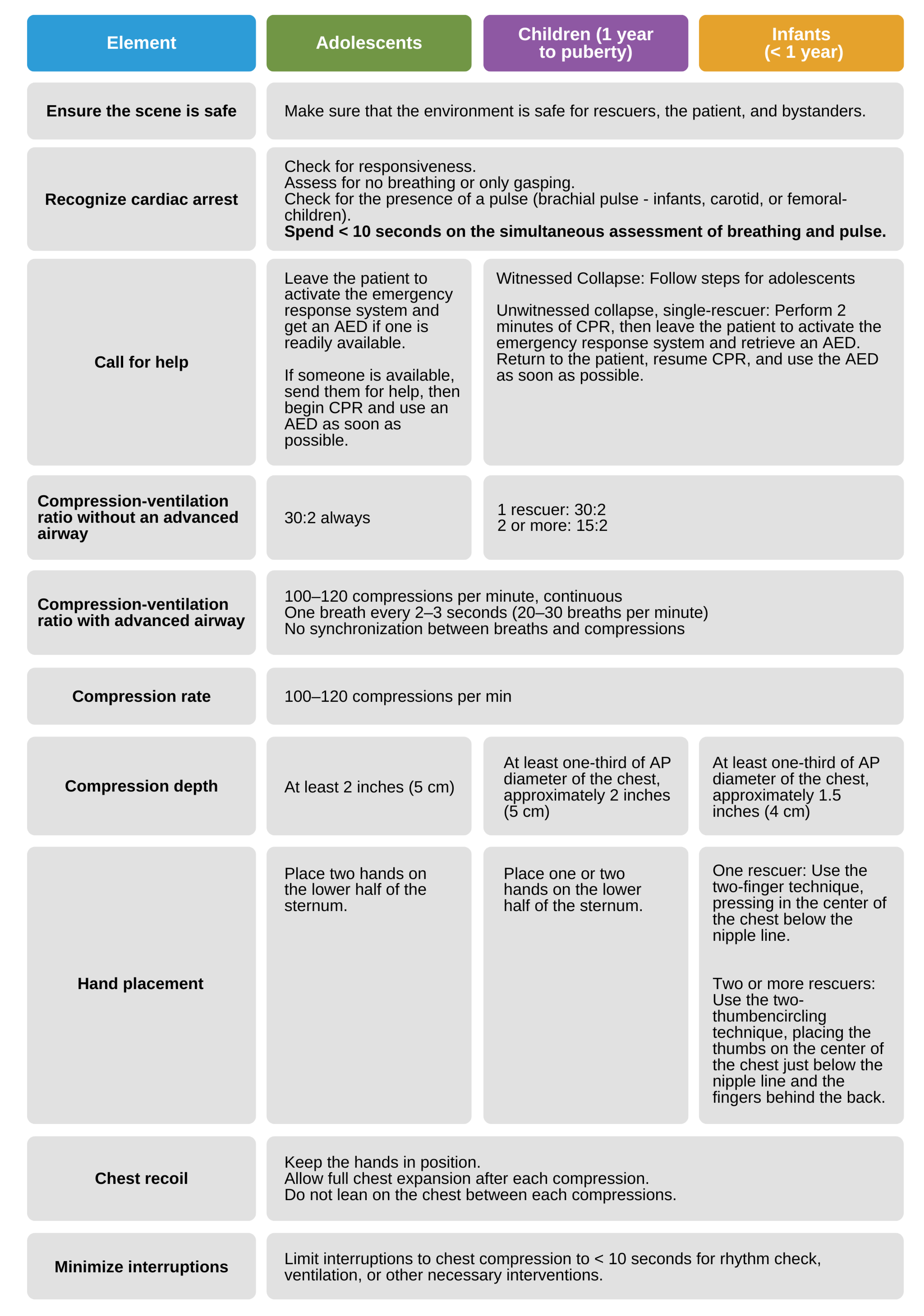

The PALS provider must be prepared to perform the basic elements of high-quality CPR to manage cardiac arrest effectively:

Basic elements of high-quality CPR to manage cardiac arrest effectively.

Monitoring the Quality of CPR

The team leader and all team members must ensure the team performs high-quality CPR throughout the pediatric resuscitation.

Key Takeaway

Compressions during high-quality CPR must be delivered:

Fast and hard

With full chest recoil

With only brief pauses

Compressions should be delivered at a rate of 100–120 per minute. Should the person performing compressions become fatigued, another team member must be prepared to step in.

In children of all ages prior to puberty, chest compression depth should be at least one-third of the AP diameter (1.5 in for infants and 2 in for children). For children who have reached puberty, chest compression depth should be at least 2 in, but not more than 2.4 in or 5–6 cm. This is the same as the recommended chest compression depth for an adult. Full chest recoil in between compressions allows the heart to fill with blood completely, and thus more oxygen is delivered to the vital organs and tissues.

Necessary interruptions to compressions, e.g., when changing compressors, providing ventilations, or inserting an advanced airway, should be < 10 seconds. Longer pauses decrease intrathoracic pressure and reduce the amount of circulation blood (oxygenated blood).

High-quality CPR requires effective, safe ventilation. Each breath should be given over 1 second and cause a visible chest rise. Ventilation must not be too quick or too forceful. A breath should be delivered every 2–3 seconds for a total of 20–30 breaths per minute.

End-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) and arterial waveforms are two means of monitoring the quality of CPR.

ETCO2 provides indirect evidence of CPR quality.21 An ETCO2 reading of < 10–15 mm Hg indicates that cardiac output is likely lower than it should be, and insufficient oxygen is being delivered to the lungs (and probably other organs as well).

If the ETCO2 is low, team members should ensure the compressions are delivered at the correct rate and depth with full chest recoil in between compressions. A sudden and sharp increase in ETC02 can indicate successful ROSC.

If the child has an indwelling arterial catheter, the amplitude of the arterial waveform on the cardiac monitor provides indirect information about stroke volume and cardiac output, markers of the quality of CPR.

20 Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S640–S656.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889

21 Hamrick JL, Hamrick JT, Lee JK, Lee BH, Koehler RC, Shaffner DH. Efficacy of chest compressions directed by end-tidal CO2 feedback in a pediatric resuscitation model of basic life support. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000450.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/JAHA.113.000450