CPR and AED Use for Adults

CPR and AED Use for Adults

Definition of the Adult Chain of Survival

The chain of survival is a framework designed for lay rescuers to provide a logical and practical procedure for handling cardiac arrest patients in community settings. Before activating the adult chain of survival, the rescuer must first determine that the patient is in cardiac arrest. The infographic below is the summary of the Adult Chain of Survival.

CPR/AED Adult Chain of Survival

The adult out-of-hospital chain of survival involves the following:

- Activation of the emergency response system (9-1-1; the phone icon)

- Early provision of high-quality CPR (the hand icon)

- Early defibrillation (the heart with a shock icon)

- Advanced resuscitation (the ambulance icon; transport to and care in the ED)

- Post-cardiac arrest care (this is handled by healthcare providers in the hospital setting)

- Preparation for recovery and rehabilitation

Providing care as a lay rescuer can be difficult because many things are missing in the out-of-hospital scenario. The lay rescuer does not have the luxury of immediately having co-rescuers within the vicinity. Also, the necessary equipment may not be available. The rescuer’s success will depend on the training, skills, and knowledge of the lay rescuer.

A person clutching the chest in pain may indicate cardiac arrest.

Activating the Emergency Response System. This typically means calling 9-1-1. The goal is to immediately summon emergency medical services to the scene of the cardiac arrest.

Immediate High-Quality CPR. High-quality CPR is emphasized because studies have shown that it increases survival rates. Skills for performing high-quality CPR are covered in the following sections.

Community Member Performing CPR

Early Defibrillation. Since ventricular fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia in the first stages of cardiac arrest, early defibrillation is key and impacts the survival of these patients.

Advanced Resuscitation. This part of the adult chain of survival involves trained healthcare providers performing advanced interventions and transporting the patient to the emergency department.

Post-Cardiac Arrest Care. This part of the adult chain of survival concerns healthcare providers only as it requires critical care management and is not part of this training manual’s scope.

Recovery. Following discharge from the hospital, rehabilitation must occur to optimize the chance of a return to full recovery.

What is High-Quality CPR?

The most important aspect of CPR is chest compressions. Chest compressions are performed with the aim to manually restore coronary perfusion pressure or, simply, blood flow to the heart in cardiac arrest patients. The intent is to enrich working heart cells with oxygen and energy so that they function again, allowing the heart to maintain a perfusing rhythm and achieve a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

Positioning of the Hands

The following are instructions for lay person rescuers to position their hands correctly:

- Find the center of the chest.

- The sternum is a solid elongated bone at the center of the chest.

- Find the middle-third of the sternum; this is the best position for the hands.

- Place one hand on top of the other, interlocking the fingers and pulling them up off the chest, so the pressure is exerting using the heel of the hands.

Positioning Hands Over the Sternum

Performing Chest Compressions

The AHA recommends that rescuers push hard and fast in the center of the chest. Lay rescuers should perform the following when applying high-quality CPR:

- Push hard: Push the center of the chest downward a depth of 5 centimeters or 2 inches. Do not exceed 6 centimeters or 2.5 inches.

- Keep the elbows extended.

- Use bodyweight to apply pressure.

- Do not use the arms as they fatigue faster; push down from the shoulders.

- Push fast: Push the chest at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute.

- Allow chest recoil: Allow the chest wall to expand fully on the upstroke of each chest compression.

- Do not lean on the chest.

- At the end of the upstroke, leave a space between the palm and the patient’s chest wide enough that a piece of paper is easily pulled out in between.

- Minimize interruptions in chest compressions: Only stop when necessary, such as doing a rhythm check or giving a shock from the AED.

Continuously reassess technique: Make necessary corrections and adjustments as needed.

Related Video: How to Perform CPR/BLS on an Adult

Each situation is unique. Position the patient in a location where there is no danger and in such a way that their back presses against a flat and hard surface. It is challenging to perform chest compressions on a bed. The rescuer should move the patient down onto the floor in the supine position when possible.

Correct Patient Compression Position

Minimizing Interruptions in Chest Compressions

Even brief interruptions in chest compressions will cause an immediate decline in blood flow to the heart and brain. It will require at least another minute of high-quality chest compressions to achieve sufficient perfusion pressure.

Interruptions should be limited to the necessary critical interventions, such as rhythm checks and assessment for spontaneous breathing; these must not last for more than 10 seconds. However, interruptions may exceed 10 seconds if more important interventions are needed, such as:

- Preparing for defibrillation

- Giving a shock

Lay Rescuer Fatigue

Fatigue may occur as quickly as 1 minute of commencing chest compressions, and it is the number one cause of failure to provide high-quality CPR. It is better if there are multiple lay rescuers. When two rescuers are present, they must switch places every 2 minutes until paramedics arrive to take over.

Related Video: Single Rescuer CPR for Adults

Compression-Only CPR

Studies comparing compression-only CPR with conventional CPR (chest compressions with mouth-to-mouth ventilation) show that the latter improves survival. However, not providing CPR at all must be circumvented. Therefore, the AHA has recommended compression-only CPR for untrained lay rescuers. When lay rescuers provide compression-only CPR, they do not need to interrupt chest compressions or check for ROSC until:

- An AED is available

- EMS has arrived at the scene to take over

- The patient spontaneously gains consciousness

Related Video: Steps of Hands-Only CPR

Hands-Only CPR

Ventilation

For at least 4 minutes after cardiac arrest (the electrical phase of cardiac arrest), the pulmonary alveoli, pulmonary vessels, heart, and major arteries will still contain enough oxygenated blood to meet the working metabolic demands of heart cells and other vital tissues such as the brain. During this timeframe, chest compressions are a priority.

If CPR has been delayed or has not improved the patient’s condition, or if the cardiac arrest was noncardiac in origin (asphyxiation or drowning), ventilation will be required.

During ventilation, the rescuer manually provides oxygen to a cardiac arrest patient and intervenes by:

- Opening the airway

- Providing positive pressure ventilation using either mouth-to-mouth breaths or by using a bag-mask device

The goal of ventilation is to oxygenate the blood by providing positive pressure breaths. The rescuer’s exhaled breath has enough oxygen to provide oxygenation to the patient’s blood. Oxygen is vital so that the working heart cells can produce energy, which is a requirement for restarting the heart.

Ventilation becomes increasingly critical in the metabolic phase of resuscitation. Lay rescuers must provide ventilation in a way that is well-coordinated with chest compressions.

Opening the Airway: Head Tilt-Chin Lift Maneuver

The head tilt-chin lift maneuver is the recommended intervention for lay rescuers to open the airway. It works by separating the tongue from the posterior pharyngeal wall to allow free airflow during mouth-to-mouth breaths. This maneuver is performed if the rescuer is sure that there is no injury to the cervical spine (the bones of the neck). Hyperextending the neck may cause more harm if there is a fracture of the cervical spine.

Anatomy of Head Tilt-Chin Lift Maneuver

Mouth-to-Mouth Ventilation

The following procedure ensures that the rescuer provides proper ventilation to a cardiac arrest patient:

- Open the airway using the head tilt-chin lift maneuver.

- Utilize a barrier device. A barrier device protects the rescuer from the transmission of disease when giving mouth-to-mouth ventilations.

- If available, use a bag-mask device.

Mouth Mask AKA Pocket Mask

- Provide positive pressure ventilation.

- Mouth-to-mouth ventilation. Form a seal around the patient’s mouth with the barrier device. Blow into the patient’s mouth for 1 second.

- Bag-mask. Form a seal over the patient’s nose and mouth with the mask. Compress the self-inflating bag in one second.

Bag-Mask Device

- Ensure adequate tidal volume.

- When there is a visible chest rise, there is an adequate tidal volume provided.

- Ensure proper timing of ventilation.

-

- Single rescuer and two rescuers for adults: Give two breaths after 30 chest compressions.

- Two rescuers (pediatric patients): Give two breaths after 15 chest compressions.

- Two rescuers with a bag-mask device:

-

- Perform asynchronous ventilation.

- Asynchronous ventilation: continuous chest compressions for 2 minutes; provide one breath every 6 seconds or 12 breaths per minute.

Related Video: Understanding Bag-Mask Usage During CPR

Early Defibrillation

During resuscitation, the most critical interventions are providing high-quality CPR, defibrillation, and rhythm checks. Early defibrillation is a fundamental aspect of CPR, according to the AHA guidelines. It is most effective if the shock is given during the electrical phase of cardiac arrest, which is the first 4 minutes after a witnessed arrest. Survival for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is < 10%, but early AED use increases survival rates to > 50%.11

Related Video: How to Use an AED

AED Hanging on Wall

Applying an AED

The following are procedures for rescuers to apply an AED to a patient in cardiac arrest:

- Power on the AED.

- Some AEDs have power switches.

- Others activate when removed from their container.

- Attach the adult pads to the chest.

- The adult pads have illustrations as to where they are placed.

- For hairy chests:

- Some kits provide razors so that the rescuer can shave the chest.

- Attach the pads with more pressure on a hairy chest if no razors are available.

- Attach the pad’s electrodes to the AED.

- The AED will voice out instructions.

- It will alert the rescuer if it is analyzing the rhythm.

- It will alert if a shock should be given.

- It will alert if the rescuer should continue chest compressions instead.

- If the AED advises the shock:

- Clear the patient: no one should touch the patient.

- Give the shock by pushing the shock button.

- The AED will alert the rescuer if a shock is already given

- After the shock is delivered, immediately perform high-quality CPR.

Related Video: Understanding Two Rescuer CPR with an AED

When a successful shock is given, the heart needs time to recover before it can regain a perfusing rhythm. Therefore, after a shock has been delivered, the rescuer immediately performs high-quality CPR for 2 minutes before performing a rhythm check. These instructions will be given out by the AED.

Adult AED Pad Placement

Special Circumstances When Using the AED

The Patient With a Hairy Chest

Hair reduces the contact surface of the AED pads to the skin. The AED will indicate that the pads are not in place if they are placed on a hairy chest. Some AED kits have razors so that the rescuer can shave on the chest. If a razor is not available, the pads should be pressed firmly to the skin to ensure good contact.

The Patient Is in the Water

Remove the patient from the water and dry off their chest before applying an AED. Electricity conducted through the water could affect the rescuer when a shock is delivered. The AED will get damaged when submerged underwater. It can operate, however, on top of a small puddle of water or snow.

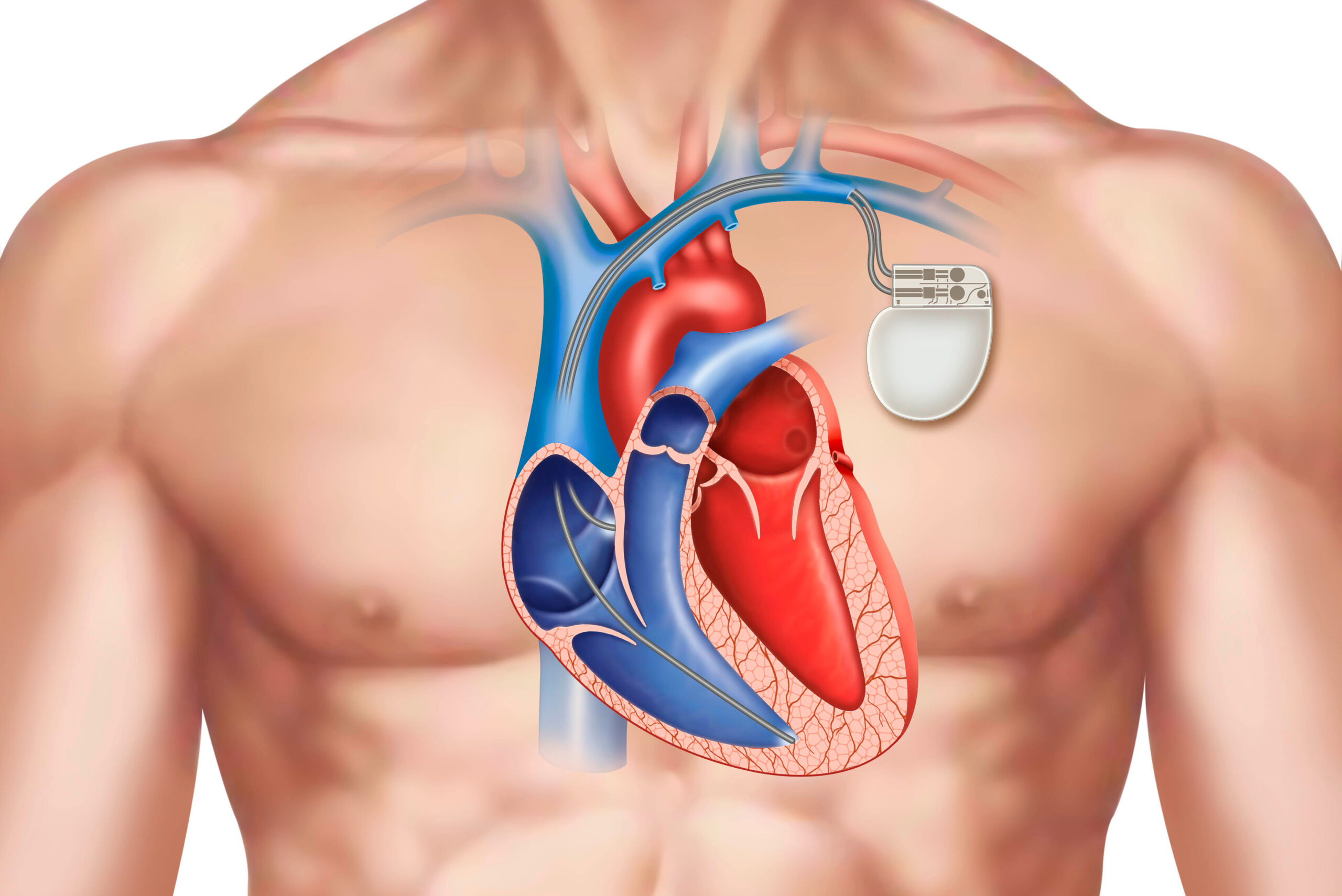

The Patient Has a Pacemaker or an Internal Defibrillator

These devices are well-demarcated under the skin. They are seen in the superior lateral aspect of the chest. The device will be rectangular and smaller than a deck of cards. The skin will likely have scar tissue from the procedure to install the device.

The typical location of the pacemaker is the upper left chest (if a person is right-handed). The pacemaker may also be placed on the right side of the chest or abdomen.

The pad should not be placed on top of the pacemaker or internal defibrillator. Avoiding placement near those implants will ensure that the shock is fully dispersed into the heart.

The Patient With a Medicinal Patch or Adhesive Bandages

Some patients may have a transdermal medication patch on their chest. These are delivery systems for drugs that are absorbed by the skin. To ensure full delivery of the shock, the AED pad should not be placed on top of a transdermal patch or bandage. Patches may burn if they meet a significant amount of electrical energy. The rescuer must remove patches and wipe off any adhesive on the patient’s skin.

Inadvertently Shocking a Patient

If a patient already has an organized perfusing rhythm, and a shock was inadvertently delivered, that shock may cause a cardiac arrest rhythm (likely ventricular fibrillation).

When a shock is delivered across 100% oxygen (from a bag-mask device or oxygen insufflation therapy), it will ignite the oxygen gas. Therefore, when providing defibrillation, oxygen sources must be moved at least 1 meter from the patient before giving a shock.

Other rare and unwanted effects from an AED include precipitation of cardiac arrhythmia, myocardial injury, and skin burns.

11 Bækgaard JS, Viereck S, Møller TP, Ersbøll AK, Lippert F, Folke F. The effects of public access defibrillation on survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation. 2017;136(10):954–965.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029067