Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

The adult cardiac arrest algorithm provides a structured, rhythm based approach to managing cardiac arrest in adults. This guide walks through the key decision points, including when to shock, when to give medications, how to deliver high quality CPR, and how to identify reversible causes. Understanding and applying this algorithm helps teams act quickly, reduce interruptions, and improve the likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation and survival.

Due to the large amount of important information contained in our algorithms, a printable PDF download link is available below.Algorithm at a Glance

- The rescuer immediately recognizes cardiac arrest and begins high-quality CPR.

- The team determines if the cardiac arrest rhythm is shockable (VF or pVT), both of which are classified as ventricular rhythms, or nonshockable (PEA and asystole).

- If the rhythm is shockable, the team administers a shock as soon as a defibrillator is available.

- If the rhythm is not shockable, the team administers epinephrine as early as possible and every 3–5 minutes after that.

- High-quality CPR continues if the patient is in cardiac arrest.

- For VF or pVT, the team considers antiarrhythmics if defibrillation is not successful.

Goals for the Management

The responder must succeed in the following goals to successfully manage cardiac arrest:

- Recognize the rhythms of cardiac arrest: ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, PEA, and asystole

- Recognize the Hs and Ts as possible causes of cardiac arrest, and strengthen your readiness with our BLS practice tests.

- Appropriately intervene in cardiac arrest depending on the cardiac arrest rhythm

Physiological Principles

Cardiac arrest care focuses on restoring perfusion and oxygen delivery to the brain and heart. High quality CPR supports cardiac output, defibrillation treats shockable rhythms, and medications support coronary and cerebral perfusion while the team searches for reversible causes. If you want deeper review, explore reversible causes of cardiac arrest using the Hs and Ts and core BLS fundamentals.

What is Cardiac Output?

This video explains cardiac output and why it matters during CPR. Understanding how compressions generate forward blood flow helps teams prioritize depth, rate, and minimal pauses.

ACLS Cardiac Output

This video connects cardiac output concepts to ACLS decision making, including how rhythm, perfusion, and interventions work together during resuscitation.

Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm Explained

During cardiac arrest, seconds matter. The adult cardiac arrest algorithm gives healthcare providers a standardized, evidence-based sequence that reduces hesitation and keeps the team aligned. When the algorithm is applied correctly, CPR interruptions are minimized, defibrillation is delivered sooner for shockable heart rhythms, and medications and airway decisions are made at the right time. This organized approach improves the chances of return of spontaneous circulation and helps protect neurologic outcomes by maintaining perfusion to the brain.

This algorithm was created to present the steps for assessing and managing patients presenting with cardiac arrest symptoms.

The ACLS responder must be able to recognize the rhythms indicative of cardiac arrest on a cardiac monitor. Understanding the basics of these rhythms allows the user to identify them quickly.

ECG Characteristics of Shockable Cardiac Arrest Rhythms

- VF – appears as voltage fluctuations on the ECG strip; amplitude is characterized as coarse (early VF) or fine (late VF).

- pVT – the patient does not exhibit a pulse; pVT appears as a fast and typically regular rhythm with wide QRS complexes on ECG and no P waves.

ECG Characteristics of Nonshockable Cardiac Arrest Rhythms

- Asystole – complete absence of electrical activity depicted by a flat line on the ECG

- PEA – exhibits an organized rhythm, but there is no palpable pulse

Box 0: Ensuring Scene Safety

Before approaching the patient, confirm the environment is safe for both the patient and the resuscitation team. Look for immediate hazards such as traffic, electrical risks, fire or smoke, chemical exposure, weapons, or unsafe surfaces. Assign one team member to manage the scene if needed, communicate clearly using closed-loop confirmation, and ensure adequate space for compressions, airway management, and defibrillation. If the scene is unsafe, do not enter until hazards are controlled or additional support arrives.

Particularly for OHCA, it is critical that the rescuer first ensure the scene is safe for both the patient and the team.

Box 1: Identifying Cardiac Arrest and Initiating CPR

Ideally, the team performs rhythm-based management of cardiac arrest. If there is no pulse, the rescuers initiate high-quality CPR. If oxygen and a monitor/defibrillator are available, the team attaches those as CPR continues.

High quality CPR means consistent compressions with minimal interruptions, correct depth and rate, full chest recoil, and avoiding excessive ventilation. Teams should switch compressors about every 2 minutes to reduce fatigue and use waveform capnography when available to help assess CPR effectiveness.

What is the recommended compression depth and rate for CPR?

For adults, compress at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute with a depth of at least 2 inches (5 cm) and no more than 2.4 inches (6 cm). Allow full recoil after each compression and keep pauses under 10 seconds for rhythm checks and shocks.

Box 2: Identifying Shockable Rhythms

If the rhythm is shockable (VF or pVT), the team proceeds to Box 3. If the rhythm is not shockable(asystole or PEA), they proceed to Box 9.

Ventricular Fibrillation ECG Review

This video shows what ventricular fibrillation looks like on the monitor and reviews the immediate priorities, defibrillation, rapid CPR resumption, and rhythm reassessment.

Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Torsades de Pointes ECG Review

This video reviews polymorphic VT and torsades patterns, and why they are treated as shockable rhythms in cardiac arrest when pulseless, with rapid defibrillation and CPR.

Box 3: Administering Shock

When using a manual defibrillator, the first rescuer performs chest compressions while the defibrillator is charging. Once charged, the rescuer stops chest compressions, and the second team member instructs everyone to clear the patient. Once everyone is clear of the patient, the second rescuer delivers a shock at the dosage recommended by the defibrillator manufacturer.

Energy Dose for Shock

- First shock – refer to manufacturer’s recommendation or highest dose available (if the recommended shock dose is unknown)

- Subsequent shocks – refer to manufacturer’s recommendations or escalating energies (higher for second and subsequent shocks)

Note: For monophasic defibrillators, the initial shock dose is a standard 360 J and for subsequent shocks.

Studies show that biphasic manual defibrillators are preferred over monophasic defibrillators for the treatment of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Biphasic waveform defibrillators set to deliver 200 J or less for the first shock were shown to be efficacious.

The first dose of shock delivery depends on the manufacturer’s recommended energy dose. If the rescuer does not know the manufacturer’s recommended dose, they should consider the maximal dose for the first and all shocks following.

If VF recurs after a successful shock is delivered, the team should deliver subsequent shocks with the same dose.

When using a monophasic defibrillator, 360 J should be used for the first shock and for recurrent episodes.

Defibrillation energy depends on whether the device is biphasic or monophasic. Biphasic defibrillators typically use a lower energy setting and are more effective at terminating VF or pulseless VT with less myocardial injury. Follow your device manufacturer recommendations whenever available.

- Biphasic defibrillation: follow manufacturer recommendation, commonly 120 to 200 J for the first shock, and equal or escalating doses for subsequent shocks.

- Monophasic defibrillation: use 360 J for the first shock and for subsequent shocks.

What are the key differences between monophasic and biphasic defibrillation?

Monophasic defibrillation delivers current in one direction and typically requires higher energy (360 J). Biphasic defibrillation delivers current in two phases, often terminating shockable rhythms with lower energy and improved effectiveness. In practice, biphasic defibrillators are preferred when available, but both are acceptable when used with correct energy dosing and rapid CPR resumption.

Box 4: Continuing High-Quality CPR

The team minimizes CPR interruptions by immediately performing chest compressions after a shock. At this point in the algorithm, it is important to obtain IV or IO (intraosseous) access in anticipation of drug delivery.

Auto-compression devices are tested on a manikin.

Clinicians should pay attention to ETCO2 monitoring.

Box 5: Rhythm Check and Shock Administration

After 2 minutes of high-quality CPR, the team rechecks the patient’s rhythm. If there is continued VF or pVT, they prepare to administer another shock. The rhythm check should be as brief as possible and CPR resumed immediately afterward.

Box 6: Epinephrine and Consideration for Advanced Airway

Once the team delivers the shock, they resume high-quality CPR immediately. At this point, two shocks have been delivered, and vascular access is available. High-quality CPR is ongoing.

It is now time to utilize drug therapy to restore a perfusing rhythm. The first-line medication for the treatment of VF or pVT is epinephrine.

A cardiac arrest patient may receive epinephrine when feasible after the placement of vascular access. Studies of IHCA patients show an increased chance for ROSC if epinephrine is given within 1 to 3 minutes of cardiac arrest as opposed to after 3 minutes.

For OHCA patients, studies show increased rates of ROSC if epinephrine is given 9 minutes or less from the onset of cardiac arrest compared with patients given epinephrine later.

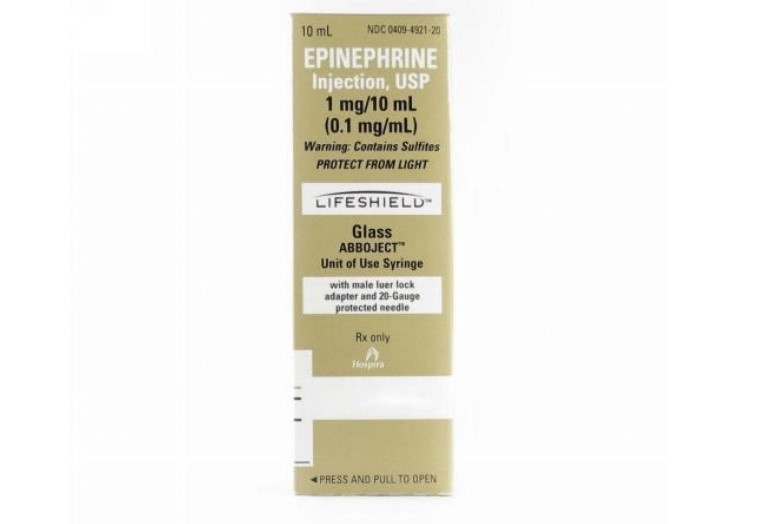

Epinephrine 1:10,000 box package revision.

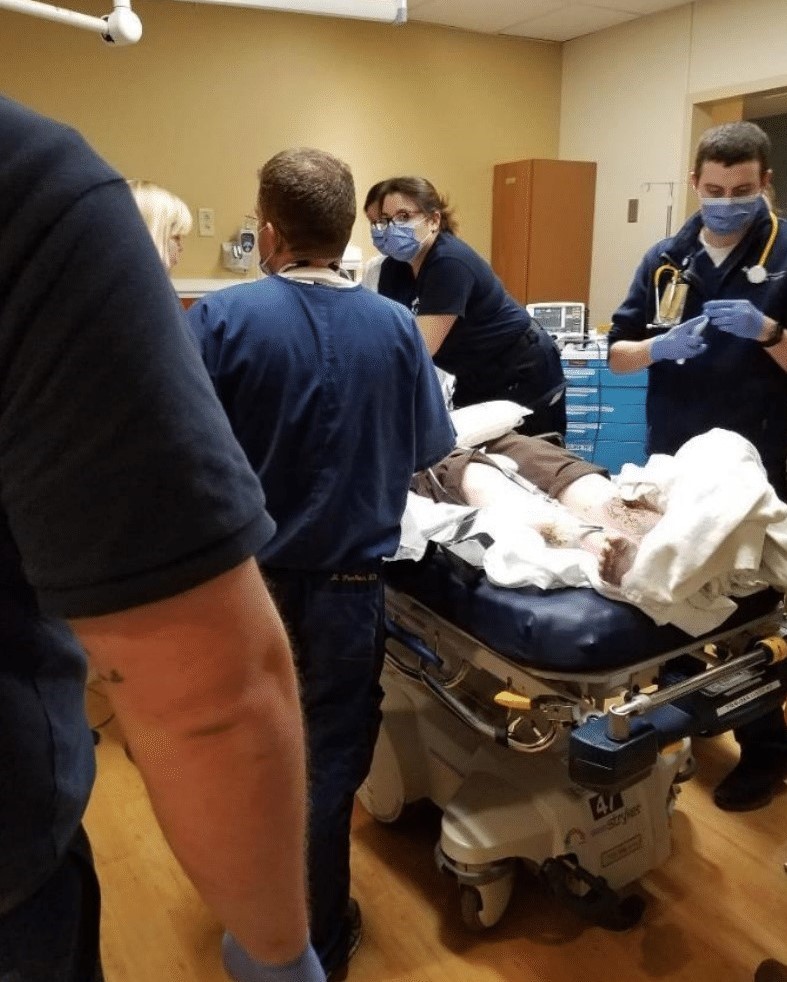

Rescuer on far right is preparing medication.

Epinephrine in Cardiac Arrest

This video reviews when epinephrine is given during adult cardiac arrest, how it supports coronary and cerebral perfusion, and how it fits into the CPR and rhythm check cycle.

Administering Epinephrine

The recommendations for treating cardiac arrest are for epinephrine intravenously or via the intraosseous route with a preparation of 1:10,000 dilution, 1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes. Studies show that this standard dose is responsible for improved survival and ROSC.

The addition of vasopressin does not deliver any advantage over using epinephrine alone. Thus, the AHA no longer recommends vasopressin as a treatment in cardiac arrest.

Common Challenges and Expert Tips

- Pauses are the enemy: keep rhythm checks and shock delivery pauses under 10 seconds.

- Compressor fatigue: switch compressors every 2 minutes and use a metronome if available.

- Over ventilation: avoid excessive breaths which can reduce venous return and lower perfusion.

- Delayed defibrillation: in shockable rhythms, early shock plus immediate CPR resumption is critical.

- Unclear leadership: assign a team leader and use closed loop communication for every action.

What to Expect During Your First Code

This video prepares new providers for the pace and team dynamics of a real resuscitation, including role assignment, communication, and how to stay organized while following the algorithm.

Key Takeaway

- Recommendations no longer suggest vasopressin as a treatment choice in cardiac arrest.

The effects of epinephrine include:

-

- Vasoconstriction, which causes increased perfusion to the heart and brain

- Increased cardiac output resulting in:

- Increased heart rate

- Increased heart contractility

- Increased conductivity of impulses through the AV node

Considering Advanced Airway

In Box 6, in addition to administering epinephrine, responders are directed to consider the insertion of an advanced airway. This is not always necessary if the patient is being ventilated adequately using a bag-mask.

For more hands on ventilation guidance, review bag valve mask usage during CPR and tips for effective bagging.

A bag mask provides manual ventilation to patients.

Ideally, two rescuers are needed to ventilate effectively with a bag-mask. One obtains a tight seal with the mask over the patient’s mouth and nose. The second rescuer delivers each ventilation at the correct time in the CPR sequence (2 breaths are given after 30 compressions) and at sufficient volume to cause the chest to rise but avoiding excessive ventilation. These are essential components of high-quality CPR.

When it is determined that an advanced airway is needed, there are several essential points the team must remember:

- Inserting an advanced airway can lead to unacceptable delays in the provision of CPR.

- Only those team members with expertise should attempt insertion of an advanced airway.

- Once inserted, proper placement must be determined by both physical confirmation (equal bilateral chest rise, air entry heard in all lung fields, and no air auscultated over the epigastrium)and physiologic monitoring (waveform capnography).

- The advanced airway is then secured in place, with placement frequently checked to detect any complications, such as dislodgement.

- Once an advanced airway is in place, ventilation and compressions no longer need to be synchronous. The compressor provides continuous chest compressions, while the ventilator provides one breath every 6 seconds.

How do you confirm advanced airway placement during CPR?

- Watch for bilateral chest rise with ventilation.

- Auscultate for equal breath sounds and absence of gurgling over the epigastrium.

- Use waveform capnography whenever available. A persistent waveform supports tracheal placement.

- Secure the airway device and recheck after movement, transport, or any CPR cycle where displacement could occur.

Note: For more information on advanced airways and ventilation during cardiac arrest, see the chapter on adjuncts.

Box 7: Rhythm Check and Shock Administration

Once the initial dose of epinephrine has been given and 2 minutes have passed since the last shock, the team pauses CPR to perform another rhythm check. If the patient’s rhythm is unchanged or refractory (patient remains in VT or pVT), another shock is administered.

Box 8: Administering Antiarrhythmic and Considering Possible Causes

Once the team administers the shock, they should immediately resume CPR for 2 minutes.

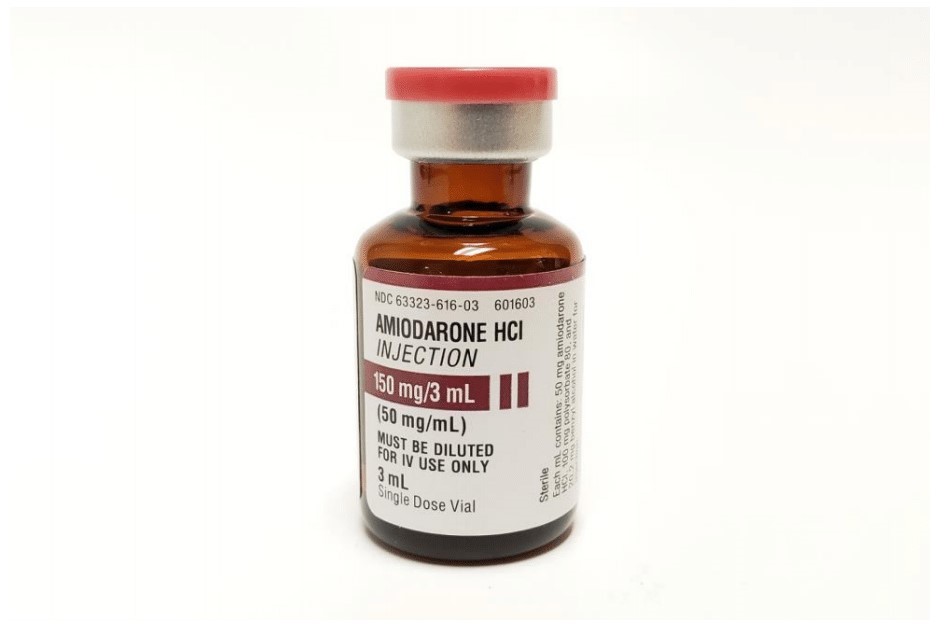

Amiodarone is given for VF or pVT refractory to defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy. Lidocaine in ACLS is an alternative treatment to replace amiodarone. Both drugs are given IV and IO.

Amiodarone is administered for VF or pVT after defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy.

Antiarrhythmic Drugs During and Immediately After Cardiac Arrest

Amiodarone is administered for VF or pVT refractory to defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy. Lidocaine is an alternative treatment for amiodarone. Both drugs may be given intravenously and via the intraosseous route.

Amiodarone in ACLS

This video explains when to use amiodarone for refractory VF or pulseless VT, and how it fits into the shock, CPR, epinephrine cycle.

Lidocaine in ACLS

This video covers lidocaine as an alternative antiarrhythmic for refractory VF or pulseless VT, including when it may be chosen instead of amiodarone.

Reversible Conditions

The team leader continues to seek and identify possible reversible causes of arrest, including

- Hypoxia

- Hypovolemia

- Hydrogen ion excess

- Hypo-or hyperkalemia

- Hypothermia

- Tension pneumothorax

- Tamponade, cardiac

- Toxins

- Thrombosis, coronary

- Thrombosis, pulmonary

Preparation of antiarrhythmic Drugs in Cardiac Arrest

- Amiodarone – First dose 300 mg IV/IO push, then 150 mg IV/IO push for subsequent doses

- Lidocaine – First dose 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg as IV/IO push, then 0.5-0.75 mg/kg IV push for a maximum of 3 doses or a total of 3 mg/kg

Box 9: Is Rhythm Asystole or PEA?

Asystole and PEA are the two cardiac arrest rhythms that are not shockable. As soon as one of these rhythms is identified, the team administers epinephrine.

Asystole ECG Review

This video shows how asystole appears on the ECG and reviews the priority actions in the nonshockable pathway, including CPR, epinephrine timing, and searching for reversible causes.

What is PEA?

This video explains pulseless electrical activity, how it differs from shockable rhythms, and why treatment focuses on high-quality CPR, epinephrine, and finding reversible causes rather than defibrillation.

Box 10: CPR Resumes for 2 minutes

The team administers epinephrine every 3–5 minutes.

At this point, the team leader considers an advanced airway and waveform capnography. After 2 minutes of high-quality CPR, the team stops briefly for a rhythm check.

Box 11: High-Quality CPR Continues If the Rhythm Is Not Shockable

The team leader assesses for treatable causes of cardiac arrest. If the rhythm is shockable at any time, the team proceeds to Box 5 or 7.

Box 12: ROSC?

If there are no signs of ROSC, the team returns to Box 10 or 11. If there are signs of ROSC, they proceed to the Post-Cardiac Arrest Care algorithm.

If return of spontaneous circulation occurs, transition immediately into post cardiac arrest care. If there are no signs of ROSC, return to the appropriate CPR pathway and continue rhythm based management.

- Confirm ROSC: palpable pulse, measurable blood pressure, rising ETCO2, or spontaneous breathing or movement.

- Optimize oxygenation and ventilation: avoid hyperventilation, target normal oxygenation per local guidance, and use capnography if available.

- Support hemodynamics: treat hypotension, establish reliable access, and consider vasopressors as needed.

- Obtain a 12 lead ECG: evaluate for STEMI and activate reperfusion pathways when indicated.

- Temperature and neurologic care: monitor temperature, assess neurologic status, and follow institutional protocols for post arrest management.

- Identify the cause: continue evaluation for Hs and Ts and address reversible factors.

Key Takeaways of the Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

- Confirm unresponsiveness, absence of normal breathing, and no pulse, then start high quality CPR immediately.

- Attach monitor or defibrillator as soon as available and identify shockable vs nonshockable rhythm.

- Shock VF or pulseless VT immediately, then resume CPR with minimal pause.

- Give epinephrine every 3 to 5 minutes and consider advanced airway and capnography without delaying compressions.

- For refractory VF or pulseless VT, add an antiarrhythmic such as amiodarone or consider lidocaine as an alternative.

- For asystole or PEA, focus on CPR, epinephrine, and rapid identification and treatment of reversible causes.

- When ROSC occurs, transition quickly into post cardiac arrest care and ongoing evaluation.

Understanding the Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

This video walks through the adult cardiac arrest algorithm step by step, showing how teams move from rhythm identification to defibrillation, CPR, medications, airway decisions, and reversible cause management. It reinforces the timing and decision points discussed throughout this article.

More Free Resources to Keep You at Your Best

Editorial Note

ACLS Certification Association (ACA) uses only high-quality medical resources and peer-reviewed studies to support the facts within our articles. Explore our editorial process to learn how our content reflects clinical accuracy and the latest best practices in medicine. As an ACA Authorized Training Center, all content is reviewed for medical accuracy by the ACA Medical Review Board.