AHA Guidelines Update: 2019

ACLS Certification Association videos have been peer-reviewed for medical accuracy by the ACA medical review board.

Table of Contents

- Overview of 2019 Changes

- Dispatcher-assisted CPR for Adults

- Cardiac Arrest Centers for Adults

- Use of Advanced Airways in Adult ACLS

- Use of Vasopressors in Adult ACLS

- Use of Extracorporeal CPR in Adult ACLS

- Dispatcher-assisted CPR for Pediatric Patients

- Use of Advanced Airways in Pediatric Patients

- Use of Targeted Temperature Management in Pediatric Patients

- Use of Extracorporeal CPR in Pediatric Patients

- Oxygen Concentration for Term Newborns

- Oxygen Concentration for Preterm Newborns

- First Aid for Presyncope

Article at a Glance

Before 2017, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) released updated advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), basic life support (BLS), and pediatric advanced life support (PALS) standards every 5 years. Since 2017, AHA and ILCOR have released annual updates to the AHA guidelines based on the best currently available scientific evidence. The AHA plans to release a full update every 5 years as in the past, but there is consensus that annual updates will ensure better patient care and outcomes.

In the 2019 annual update, changes were made in the following sections of the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), BLS, ACLS, PALS, Neonatal Resuscitation, and First Aid guidelines:

- Dispatcher-assisted CPR for adults

- Cardiac arrest centers for adults

- Use of advanced airways in adult ACLS

- Use of vasopressors in adult ACLS

- Use of extracorporeal CPR in adult ACLS

- Dispatcher-assisted CPR for pediatric patients

- Use of advanced airways in PALS

- Use of targeted temperature management in PALS

- Use of extracorporeal CPR in PALS

- Oxygen concentration for term newborns

- Oxygen concentration for preterm newborns

- First aid for presyncope

Overview of 2019 Changes

This document provides the recommended changes to the guidelines in the 2019 annual update. Unless changed or replaced in subsequent guidelines, these recommendations should be considered current.

The 2019 update summarizes published evidence regarding the use of advanced airways, vasopressors, and extracorporeal CPR during cardiac arrest.

“}” data-sheets-userformat=”{“2″:4224,”10″:2,”15″:”Arial”}”>

Dispatchers should offer CPR instructions and be empowered to instruct callers to initiate CPR for adults suspected of being in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).1 Recommendation: dispatchers should provide compression-only CPR instruction for adults with OHCA. Dispatchers should provide compression-only CPR instruction for adults with OHCA. If a caller reports an adult patient experiencing cardiac arrest, dispatchers should offer CPR instructions.Dispatcher-assisted CPR for Adults

2019

2017 (Old)

2015 (Old)

Regions should use an area-wide approach to post-cardiac arrest care by transporting OHCA patients to specialized cardiac arrest centers.2 Regions should consider using an area-wide approach to post-cardiac arrest care by transporting OHCA patients to specialized cardiac arrest centers. Read: Understanding the 2020 AHA Updated GuidelinesCardiac Arrest Centers for Adults

2019

2015 (Old)

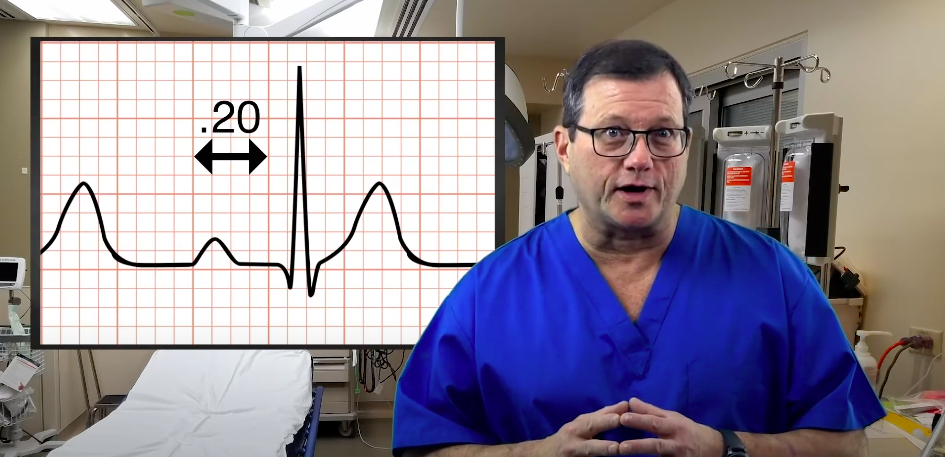

A bag-mask device or advanced airway may be used during CPR in any location. A supraglottic airway is preferred in out-of-hospital settings with limited endotracheal (ET) intubation success or where training is not readily available. A supraglottic airway or ET tube should be used in out-of-hospital settings with high success in endotracheal intubation and where training is available and ongoing. A supraglottic airway or ET tube should be used in in-hospital settings with providers experienced in the procedure. For any provider inserting an advanced airway, frequent training is recommended. Pre-hospital systems should have tracking mechanisms in place to track success rates with advanced airways. A bag-mask device or advanced airway may be used for a trained provider during CPR in any location. For any provider inserting an advanced airway, frequent training or experience is recommended. Pre-hospital systems should have tracking mechanisms in place to track success rates with advanced airways.Use of Advanced Airways in Adult ACLS

2019

Related Video – What are Ventilation Devices?

2010 and 2015 (Old)

The clinician should know that it is reasonable to give epinephrine at a dose of 1 mg every 3–5 minutes. High-dose epinephrine is still not recommended.3 It is also reasonable to give standard-dose epinephrine as soon as possible in a cardiac arrest due to a nonshockable rhythm. The clinician may consider vasopressin as a substitute for epinephrine in a cardiac arrest scenario; however, there is no evidence to suggest that vasopressin is a better option. The clinician may consider vasopressin combined with epinephrine in a cardiac arrest scenario. However, there is no evidence suggesting that this combination is a better option. It may be reasonable to give epinephrine at a dose of 1 mg every 3–5 minutes. High-dose epinephrine is not recommended. It may be reasonable to give standard-dose epinephrine as soon as possible in a cardiac arrest due to a nonshockable rhythm. There is no evidence to suggest that vasopressin is useful as an option for epinephrine in cardiac arrest. There is no evidence to suggest that vasopressin, in combination with epinephrine, is useful as an option for epinephrine alone in cardiac arrest.Use of Vasopressors in Adult ACLS

2019

Related Video – Epinephrine – ACLS Drugs

2015 (Old)

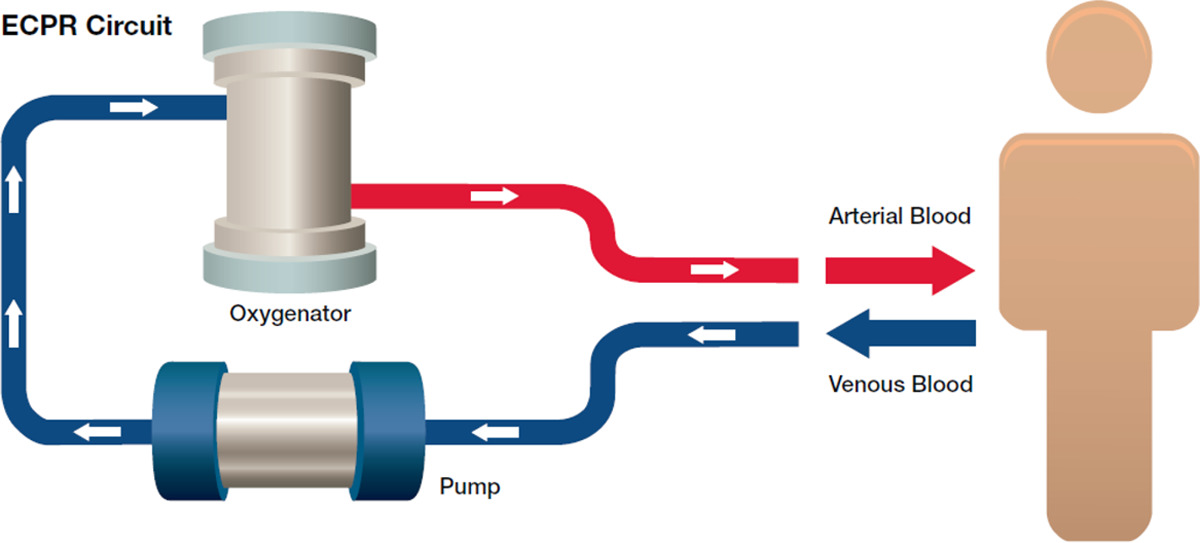

The evidence is insufficient to support extracorporeal CPR (ECPR) in cardiac arrest. However, the clinician might consider its use when conventional CPR is not working.4 The clinician might consider the use of extracorporeal CPR in scenarios where the rescuer suspects a reversible cause and when ECPR might provide support. The evidence backing extracorporeal CPR (ECPR) is inefficient, but it might be considered when conventional CPR is not working.Use of Extracorporeal CPR in Adult ACLS

2019

Related Video – ECMO Explained – What is It and How It Works

2015 (Old)

Dispatchers should offer instruction in CPR for pediatric cardiac arrest when bystanders are not performing CPR.5 There is no recommendation for offering CPR instruction when bystanders are performing CPR.Dispatcher-assisted CPR for Pediatric Patients

2019

In an OHCA, the pediatric patient responds as well with bag-mask ventilation as with the insertion of an advanced airway. There is no recommendation about the use of an advanced airway for in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA). There is no recommendation about which advanced airway is preferable in IHCA or OHCA. The out-of-hospital team should ventilate children with a bag-mask device.Use of Advanced Airways in Pediatric Patients

2019

2010 (Old)

The team should continuously monitor the child’s temperature during targeted temperature management (TTM). The clinician should maintain the temperature between 32–34°C, followed by TTM of 36–37.5°C.6 A second option is simply to maintain a TTM of 36-37.5°C. There is no recommendation for how long treatment should last, but studies have been done using 5 days as the length of time. In a pediatric patient, a temperature greater than 38°C should be aggressively managed. The recommendation was that it is reasonable to maintain normothermia for 5 days or 2 days of hypothermia followed by 3 days of normothermia.Use of Targeted Temperature Management in Pediatric Patients

2019

2015 (Old)

The clinician might consider extracorporeal CPR in IHCA pediatric scenarios where the child has a cardiac diagnosis, assuming that there is expertise and appropriate equipment in the hospital setting. There is no recommendation for the use of ECPR in an OHCA or in scenarios where the child does NOT have a cardiac diagnosis. The clinician might consider ECPR in IHCA pediatric scenarios where the child has a cardiac diagnosis and expertise and equipment are available.Use of Extracorporeal CPR in Pediatric Patients

2019

2015 (Old)

For newborns ≥ 35 weeks gestation who are being supported for respiratory issues at birth, it remains reasonable to begin ventilation with 21% oxygen concentration.7 The clinician should not use 100% oxygen. For newborns ≥ 35 weeks gestation, ventilation should begin with 21% oxygen concentration titrated to a preductal oxygen saturation in the interquartile range for healthy term newborns.Oxygen Concentration for Term Newborns

2019

2015 (Old)

For newborns < 35 weeks gestation who are being supported for respiratory issues at birth, it remains reasonable to begin with 21–30% oxygen concentration. The clinician should titrate the concentration based on pulse oximetry results. For newborns < 35 weeks gestation, oxygenation should begin with 21–30% oxygen concentration titrated to a preductal oxygen saturation in the interquartile range for healthy term newborns.Oxygen Concentration for Preterm Newborns

2019

2015 (Old)

A patient who experiences presyncope (dizziness, sweating, nausea or vomiting, blurred vision, or altered mental status) should first be encouraged to move to a sitting or lying position in a chair, bed, or on the floor. A first aid rescuer can encourage the patient to contract muscles in the legs and arms to increase the blood pressure. This should not be suggested if other symptoms may indicate a possible stroke or heart attack. If initial first aid is not successful, the first aid provider should initiate the emergency response system. This article provides a summary of the 2019 AHA guidelines updates.First Aid for Presyncope

2019 (New – no previous recommendations)

Related Video – How to Reach EMS

More Free Resources to Keep You at Your Best

Editorial Sources

ACLS Certification Association (ACA) uses only high-quality medical resources and peer-reviewed studies to support the facts within our articles. Explore our editorial process to learn how our content reflects clinical accuracy and the latest best practices in medicine. As an ACA Authorized Training Center, all content is reviewed for medical accuracy by the ACA Medical Review Board.

1. American Heart Association. Systems of Care.

2. Brian L. Chang, MD, Mary P. Mercer, MD, MPH, Nichole Bosson, MD, MPH, and Karl A. Sporer, MD. Variations in Cardiac Arrest Regionalization in California. National Library of Medicine. 2018.

3. American Heart Association. Circulation.

4. Hongsun Kim and Yang Hyun Cho. Role of Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults. National Library of Medicine. 2020.

5. Miranda Lewis, Benjamin A. Stubbs and Mickey S. Eisenberg. Dispatcher-Assisted Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. American Heart Association. 2013.

6. Alex Koyfman, MD. Targeted Temperature Management. Medscape. 2019.

7. American Heart Association. 2019 American Heart Association Focused Update on Neonatal Resuscitation. 2019.